China is winning the media war

Thanks to censorship, a new media direction, and Western self-sabotage, today the stories you hear from China.. are mostly just those the Party wants you to hear.

Whisper it, but something is happening.

Last week, The Economist, not a magazine prone to hyperbole, published a startling headline: “How China became cool.”

The article surmised China’s PR wins this year, like: Deepseek, RedNote, and IShowSpeed’s streaming success. “Increasingly, more people, especially younger ones, seem willing to look past China’s ugly side,” it noted.

More startling too are recent polls, like that by the Alliance of Democracies Foundation. Since 2022, global opinion of China has risen from -4 percent to +14 percent. The US, meanwhile, has dropped from +22 percent to -5 percent in just a year.

China Daily fell over itself to reprint and translate the Economist article in full. “The rise of China's soft power is a quiet but profound shift in the global narrative,” it cooed.

The reality is a little more mixed, but it’s also not far from a truth people should probably start addressing.

… China is winning the media war.

‘Show our swords’

You may feel “war” is a strong word.

I promise you: it’s no less than the type of language used behind doors in Beijing, and publicly too, sometimes. Like on Feb 10, when China Media Group — China’s largest, and most prominent foreign-facing media organisation — held its annual work conference.

“We must continue to improve our ability to fight from offense to defense, and effectively carry out the struggle and guidance of public opinion against the United States and the West,” said CMG Editor-in-Chief Shen Haixiong, in a rallying speech to attendees.

Shen is also Deputy Minister of the Government Propaganda Department, by the way. And the article notes his words “conveyed the instructions of the central leadership”.

Or how about this excerpt from "China's Rise: Public Opinion War" published by People's Daily.

If military strategists used to say "before the troops move, the food and grass must go first", then today, in the highly developed information age where everyone is a media, everyone has a microphone, and everyone has a camera, it is obviously more realistic, urgent, and important to say "before the troops move, the public opinion must go first"

“We must dare to show our swords, identify our targets and take the initiative to attack,” he adds in a later chapter.

The writer is Ren Xianliang. Today he heads the World Internet Conference, which works to establish rules for the Internet, and AI. Comforting.

The terminology doesn’t stop there. A key facet of the China’s current communications strategy is to build an army KOL’s — state-backed influencers, who hide their origins, and steer “opinion guidance” via short videos. Their nickname? China’s “light cavalry”.

The state has bet big on these. And in the next few weeks, I’ll be looking a bit closer at some of these “riders”, and how they operate, including (spoiler) right here on Substack.

The CPC knows it is in a media war. And it knows exactly who its enemy is.

But is it working?

“Not good at telling stories”

China’s public global image is coming back from catastrophic record lows — lows that it, itself, largely instigated.

Hong Kong. Xinjiang. Covid. But also Wolf Warriorism, the Party’s attempt at aggressive, confident rhetoric (full story here). That was the Party trying. It was supposed to the moment China stood up. Instead: it fell on its face.

Why? The truth is savage.

In my personal experience, so inept are some Chinese state media workers, so unable to grasp foreign audiences, or fashion leaden Party themes into a palatable product, many would have a much greater positive impact on China’s reputation if they simply stayed home every day, and not bother go to work at all.

The recent trend of only hiring idealogues and sycophants has only made the industry more out of touch with the rest of the world.

Don’t take my word for it. Ask Sun Shangwu, Deputy Editor-in-Chief of China Daily.

“Some subjects are not good at telling stories in international communication practice, and their communication skills and empathy need to be improved,” he said in an article last October. Ouch.

In an understatement, he added: “China's existing international communication system does not match China's comprehensive strength and international status”.

He should know. Look closely, and you’ll see that — on his watch — numbers are down across many of his outlet’s public accounts.

Some China Daily videos — produced at great cost, time, and effort — now go out to tens of views on some platforms. That’s not a typo. Tens.

Bot farms and batch-bought ‘likes’ disguise some of the shame. Like the one currently featured at the top of its Facebook page (supposedly 144 million followers). At writing, the video claims to have over 500 thousand views, and 2,200 likes. The fact it has only five comments? That’s the giveaway.

The same is happening at other outlets. State media simply isn’t connecting.

But media has made a fundamental change. As covered before, over a year ago, Beijing started to reject its more belligerent approach and move back toward “good news”, and “positive vibes”.

Output today may be banal, shallow slop, oft fronted by cheap day hires: “Food tasty. Robot clever. Panda cute. Bridge big. Xi wise. Party cuddly.” — but at least it is innocuous.

For half a decade, Chinese state media tried to force bitter pills down foreign throats. Now, it appears, they serve placebos: harmless doses, that have absolutely no measurable impact whatsoever on the world. The patient isn’t recovering, it’s just no longer being poisoned.

Possibly more impactful however, has been the Party’s effect on the foreign press.

Western reporters, look away now.

Western castration

Today, China-based foreign correspondents are largely an extinct species.

Doxxing. Stalking. Online harrassment. Campaigns directed at them by state media. It’s no wonder why the industry has been rocked by high profile exits in recent years.

In 2020, the BBC’s John Sudworth left after he came under intense backlash following his reporting in Xinjiang; he and his family were followed to the airport by plain clothed police officers. And too the ABC’s Bill Birtles, who visited by six policemen at his home at midnight. He spent four days camped in the Australian Embassy, before he was allowed to leave China for good.

Beijing has also stymied those coming in.

According to the Ministry website, it “normally takes 15 working days” for it to issue permission for a journalist visa. But in reality, it has taken some outlets a year or more. No reason is given for the delays. Media note that often, the more competent a candidate they submit, the longer the delays can be. Almost as if there is a deliberate plan to dilute Western reporting effectiveness.

For those that get in, the games are only just beginning. The duration of their visas can be as short as a month. Renewal is a constant headache. During Covid, one said they only had their visa renewed with hours to spare — the confirmation arrived as they were literally in the cab on the way to the airport.

Journalists tell me they feel this is deliberate tactic by Beijing to demoralise and distract them. A sword of Damocles forever over their head. “You are here, but only if we choose.”

Behind the scenes, many newsrooms, have beat a retreat, preferring instead to report from afar in cities like Taipei, Seoul, London and Washington. This, obviously, is no substitute. Content has suffered. And they have become reliant on second-hand sources.

A dirty secret was brought painfully to light this year: just how reliant the Chinasphere is on governmental, and quasi-governmental funds.

It’s not gone unnoticed how many “independent” media, researchers, campaign groups and vloggers have folded since USAID imploded in January. In particular, stories on democracy protestors, human rights campaigners, and transnational repression have slowed.

(Full disclosure: not me. I’m just an independent guy in an attic. *Rattles tip jar.*)

While it’s been an open secret for some time that many prominent faces / outlets in the sector were reliant on hidden funds, what did raise eyebrows is just how much some earned. Well into six figures per year, according to leaked files online.

There’s also truth to China’s allegation it is targeted by deliberate smears.

A number of journalists — based outside of China — have told me they’ve pitched neutral stories to their editors, only to be shot down. “Get me China bad,” one surmised. I, too, have experience that.

The impact is that China reporting is currently in a death spiral.

Viewed from afar, Western media is often working against itself.

Foreign journalists abroad, unable to fact-check or add nuance, are crafting hyperbolic, sometimes error-strewn reporting, to meet “China bad” narratives, which are perpetuating anger and disillusion by Chinese citizens, a disquiet that is fanned by the Party, and directed at China-based reporters, and inspires them to further timidity and cowardice.

“Every time a journalist back home cocks up, we get the consequences,” one Beijing-based correspondent told me anonymously.

They went on to explain how in one instance, they had researched, shot and edited a piece about Xinjiang — only for the China Bureau Chief to spike the piece at the last moment, scared of causing trouble.

It’s a losing circle.

Cast your mind back over the past year, and count the number of explosive investigations that actually held the CPC to account, made Beijing squirm.

I’ll give you a minute.

Instead, many China-based correspondents are fearful, and sticking close to Beijing. They busy themselves in day-to-day politics, the movements of President Xi, and Beijing’s official response to news abroad. In effect, they are nothing more than diarists. When they do venture out the capital, they are eschewing knotty stories for fluff, like the “China’s EV market”, or “Russian stores opening in China”.

A few months back, I attended a talk featuring a panel of China Correspondents. “Are media pulling their punches?” I put my hand up and asked. “No. Of course not,” the panel roundly agreed publicly on stage.

“Yes, definitely,” one or two later whispered in my ear.

No one is enjoying this blunting more than the Party.

“Why can real China be seen in some Western media reports recently?” ran a headline Global Times in February — the tabloid seemingly so quick to gloat, it forgot to proofread.

But perhaps, China’s greater wins are coming online.

Convince or destroy

[China’s] intellectual leadership is moving toward liberalism, the traditional media are opening up, and the internet is becoming a cultural arena which the state is too clumsy to effectively conquer.

“Why China Will Democratize”. Liu Yiu and Dingding Chen. Columbia University. 2012

Many prophesized that the Communist Party of China would never be able to outrun the internet. That liberty would prevail. How wrong.

Last year, China spent 225 billion yuan on “public safety” — one-and-half times more than it did on education. It has built the world’s most sophisticated online censorship tools. Its press has been purged, and sworn fealty to the Leadership. And more than that — it has instilled self-censorship in the minds of its citizens.

What practically no one foresaw, though, is China breaking out from behind its Great Firewall to disrupt Western social media platforms, too.

Take Twitter.

Very few people will know what actually motivates drug-addled, sleep-deprived Elon. Yet for China, he has been the ultimate long-term bet.

When the CPC donated a multitude of tax breaks to Tesla, leading to its Shanghai gigafactory, China’s aim was nakedly obvious: technology transfers. Almost single-handedly, Musk has helped the Chinese automotive industry skip generations, to now lead the NEV world.

Yet not even in their wildest dreams, did China’s leaders also imagine Musk would also help them one day neutralize Twitter, and deliver a direct whispering channel into Trump’s highly susceptible ear.

Musk’s attempts to rid Twitter’s “woke mind virus” has been ruinous.

In Europe, according to X’s own figures, the platform lost 11 million users last year. In countries closer to the Ukraine war, and so more sensitive to Musk’s increased Pro-Russia narratives, the fall is even more stark. Romania lost 37 percent of its monthly logged in users, Poland 40 percent, and Lithuania over 60 percent.

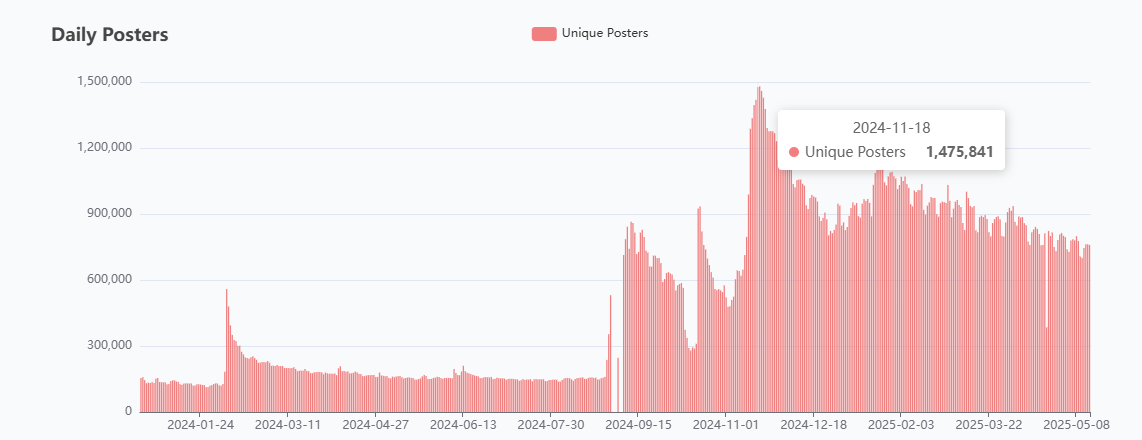

These numbers are even more damning when you consider they include bots — around two thirds of all accounts — according to one research of a million accounts. Since Musk's takeover, there has been an explosion in spammification, bot networks, and influence campaigns. Many from China. And aimed at amplifying Beijing’s messages.

The primary objective for the CPC was to conquer the platform, sway minds. If the degradation of the platform drove actual users away — well that too is an outcome.

Convince or destroy.

My first scribble here — “As BlueSky takes flight, China has got a Twitter problem” — was based on a tip off; a social media manager at a prominent state media outlet told me this was indeed a headache for them.

In hindsight, they needn’t have worried. That take was already out of date.

Four days earlier, BlueSky hit its peak of around 2.8 million likes per day. Today, it’s half that number. Users haven’t flocked to the platform: they’ve left.

Bluesky. Substack. Threads. The truth is: the journalistic, research community that once thrived on Twitter are currently scrabbling. Unable to coalesce, many are simply drifting offline. Bonds are being broken, and the journalistic world is fracturing.

Much attention was given to RedNote when it topped the app charts, but I was less enamoured.

“Rednote will be a two week love affair for westerners. The ‘new Tiktok’, will probably be Tiktok,” I wrote at the time.

But while I was cynical about app’s long-term popularity, like many others it couldn’t help but be struck by something key. Just how easily swayed many “TikTok refugees” were.

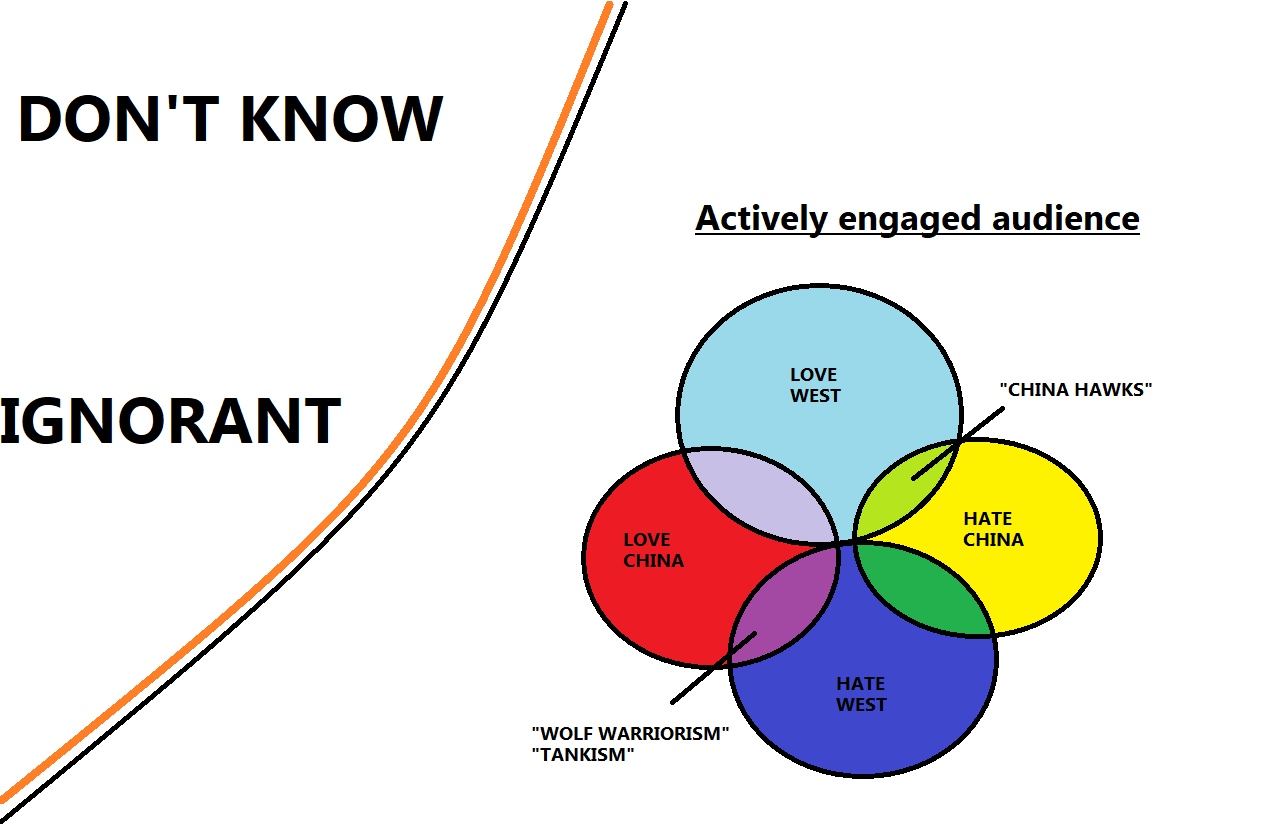

Here’s the rub with China: Most people know absolutely nothing about it.

A China word cloud for the average person in US, Europe might read something like: “dystopian” “dictatorship” “food” “slave labour” “polluted” ”poor”, thanks to reports that’s wafted by them.

These preconceptions have always been fragile ones. As all the PRC needs to do is show reverse examples. And the country is plenty big enough, and developing fast enough, to find some.

I’ve long argued that this “ignorant” demographic is the key to China’s long-term PR success. This is the rich vein that IShowSpeed, TikTokRefugees and other Youtube streamers are currently tapping, to huge numbers.

At China Daily once, when frustrated with some of the godawful nationalistic coverage a colleague was doing, I drew them a chart of overlapping circles. “Look. These are the people you’re currently targeting,” pointing at the teeny, tiny segment where “Love China” met “Hate West.

“Sure. You like them, because the few people who read it are passionate, comment lots, and they swallow your nationalistic, chest-beating bullshit.”

“But these are the people you want to target,” drawing a massive circle, “Don’t know / Ignorant”.

“They’re harder to reach, but but bigger in number, and easier to influence. You just got to speak on their terms.”

“And every time you target one of these idiots…” I jabbed my finger aggressively back on ‘Wolf Warriors’, “you conform to every negative preconception about China, and state media — and you push one hundred of these (Ignorant) away from me.”

“Stop making my job harder.”

This, then, is a bittersweet moment for me. It’s taken five years, but the penny is finally dropping for the Party. Someone, somewhere, probably in the Zhongxuanbu, is winning plaudits, and no doubt some fat hongbaos, for what is essentially common sense.

Whether the state can advance this “soft power”, thanks to its inept media (see passim), or a visa-free scheme that is yet to deliver the hoards of foreign tourists (arrivals are still below pre-Covid levels), or in spite of its clod-footed desire to insert itself into everything… at least, for now, the Party is walking the right path.

Conclusion

Truth is, I too am a coward. This post has been a long time coming. According to the timestamp, I scribbled the title down on January 21st. But, especially as the Trade War got underway, I held off for fear of getting it so very, very wrong.

Also, the sun was out.

But the more I’ve looked, read, and asked around, the more I’ve realised the causes behind China’s warming are systemic. Today’s situation has been years in the making, and — failing a big bang event — would take years to reverse.

The truth is, yes, China is beginning to win the media war, but it is doing so by partly by default.

Mostly, the West has crippled itself.

Capacity — already laughably small for covering a country the size and importance of China — has been further decimated by cuts to key services, like: USAID, or the BBC Global Service.

Content: by fetishising negative coverage, that has backfired with Chinese people, who feel under attack from foreigners.

By sloppiness: hastily thrown together hit pieces from afar, that leave holes for the Party to surgically exploit, and shred Western media credibility.

Or by geopolitical hypocrisy: Western leaders pushing values they themselves fail to practice.

It would be hasty to read this current time as a mere thaw, a temporary correction from China’s historic PR lows.

The underlying fundamentals suggest we’re entering a new paradigm. One where the CPC has locked down its information sphere sufficiently enough, that it can allow only the stories it wants you to hear. The West, meanwhile, is reaching the point it lacks the will or capacity to penetrate that wall.

Which leads to a question.

China knows it is in a media war, does the West?

Thank you for reading~

I’ve actually been coaxed out from my attic, and in a VERY RARE occurrence, will be joining a panel of interesting peeps next week to discuss *reads passed note*: “Reporting, State Media and Journalism in China”. Come for the others. I’ll be sharing some stories too. And if the beer is lovely, maybe even some I probably shouldn’t.

Tuesday 3rd June. 7pm. Frontline Club. If you’re in London, swing by. Ticket details here.

Good take, though there is a little bit of a contradiction in the end. You bemoan that often editors outside China want “bad China” stories, but at the same time complain about correspondents in the country going for “fluffy” and none controversial stories to avoid harassment and trouble. Out of my own experience I can say it’s a delicate dance, but what would be noticed also is that on the ground the CN government is increasingly successful boxing-in foreign journalists. Despite at times still willingness to go for the more edgy stories it is increasingly difficult to actually get anyone to talk to you, even anonymous.

Once again, another great read. I remember having similar conversations — I think my exact words (translated) were: “If you keep this up, China will be able to count the number of its friends on half a hand”.

Another thing that some people may not know: many employees of state owned enterprises (and especially state owned media) are supplied with company-issued phones with a built-in VPN and pre-installed Western apps. Commenting on chosen topics with set narratives are part of their KPI. The people I knew who had them hated this job. They probably just use AI to formulate comments for them now.

Also, corruption can be seen through state owned media’s social media practices. For example, an outlet might win a contract from the propaganda department, and take 50 million. Probably 45 million of that goes to… who knows what. In Guangdong, it was property investment. The other 5 is shared amongst departments, and then a measly budget of 250,000 gets allocated to producing the content for a year. Then, these outlets post content to platforms where it is easy to fake numbers by buying likes or paying for promotion, and those inflated numbers get written into reports that go back to the government so that the contract can be renewed and the whole cycle starts again.

“That’s corruption”, I said when I heard my colleagues talking about it. “No it isn’t,” they said, “because everyone does it.”

I once worked on a television project exactly like this. We were all excited when our department won a contract worth tens of millions to produce travel content (less political, fun to go out and produce with colleagues).

Then, the budget for EACH episode was set: 4,000 yuan per episode. That’s for filming, presenters, editors, etc. We weren’t happy with that and half-arsed it, and only filmed in places we could drive to within an hour.

Of course, there was a secondary budget, which went to “executive producers” and “supervisors”, all people who contributed nothing other than giving the episodes the tick of approval to go out. Or not even that. And the people producing the shows never got a look at that budget, either, of course.

And, if any of those shows were to ever win an award, those names always listed first.

I once produced an episode that did win an award. I was shocked to see that the nomination had left my name out — there was room for only four names, and three leaders needed to be there, and then a “supervisor” decided to put their name there instead of mine. I presented & produced the show, along with a camera operator who also edited it.

I had to kick up a stink to get my name on there (the final solution? Tweak the rules so five names could be on there… what was all the fuss about?), and apologised profusely to the camera operator. He was fine about it — said he’d rather not be named. I shared my bonus with him for winning the award (after the other four people took their “share”), and he appreciated that.

Not only was the budget minuscule, it often took MONTHS to get paid/reimbursed. I never had any trouble getting people to work with me on projects, because I paid them out of my own money on the day, and took on the risk of delays/denials in payment personally. People do appreciate you when you treat them with respect and dignity, and not just say, “I’ll pay you if and when I do.”

And another interesting thing I’ve seen recently: state owned media outlets (including the one I used to work for) have been cooperating with the Western media outlets that they once derided, like the BBC, on producing documentaries.

And during COVID, it was like China couldn’t make up its mind: did it hate the Western press, who only pedal lies, or did it love the Western press when something remotely positive was said about China?

There was one day, in particular, where the narrative nation-wide was “BBC grey filter! Lies! Smears!”, while in Guangdong, one of the top stories of the day was “Guangdong’s Chaozhou shines on the BBC and becomes known by the world”, after a short segment about the city was aired on the channel.

Or, while Beijing was actively blocking visas for journalists, provincial governments were quietly offering outlets bureaus in provincial capitals with assurances that visas would be expedited, etc.

Part of me agrees with your take, that China is winning in a media war, but another part of me feels like it isn’t — at least it hasn’t made any solid ground — the world is just distracted by other, more pressing issues, such as the ongoing invasion of Ukraine, the terrible loss of life in Gaza, and civil wars in Africa. Plus, the U.S. isn’t exactly a beacon of sanity and order at the moment.

China, I think, certainly isn’t winning, it’s just been given a breather. And it’s not making the most of this lull in a focus on China’s shortcomings. A friendlier, more approachable China would probably be welcomed by the world right now. But that hasn’t materialised.

If the Western media and legacy media are struggling to find their audience, I doubt China would be any more adept at doing the same.

China does have the talent and the means to portray itself in a better light, but around 2019-2020 when a generation of leaders at departments & news centres nationwide retired, ideologues were prioritised over whoever was actually in line for a promotion.

The system rooted out anyone with a hint of liberal values, or any form of professional journalistic standards — and those who remain keep their heads down in hopes that things will one day change again. I admire their resilience.