Is China's "peak coal" just spouting emissions?

In many ways, coal is the Party's biggest, dirtiest secret. Long read.

For some, last year was supposed to be China’s year for ‘peak coal’. It wasn’t.

“It's looking very likely now that 2023 will end up being declared the year of peak coal in China. We won't know until we see 2024 decline, of course (and 2025, and every year thereafter),” analyst David Fishman excitedly tweeted in July 2024.

“If you'll indulge in me wrapping this up with a little self-congratulations, I've been predicting 2023 would end up being China's coal peak as early as Sept last year,” he added.

I remember reading that with cynicism at the time. For as good as Fishman is on the ins of the Chinese energy industry, he’s also somewhat, let’s say — blinkered — on China as a whole. (Take this thread where he explains how he chooses his friends.)

For me, it simply didn’t chime with wider macro factors.

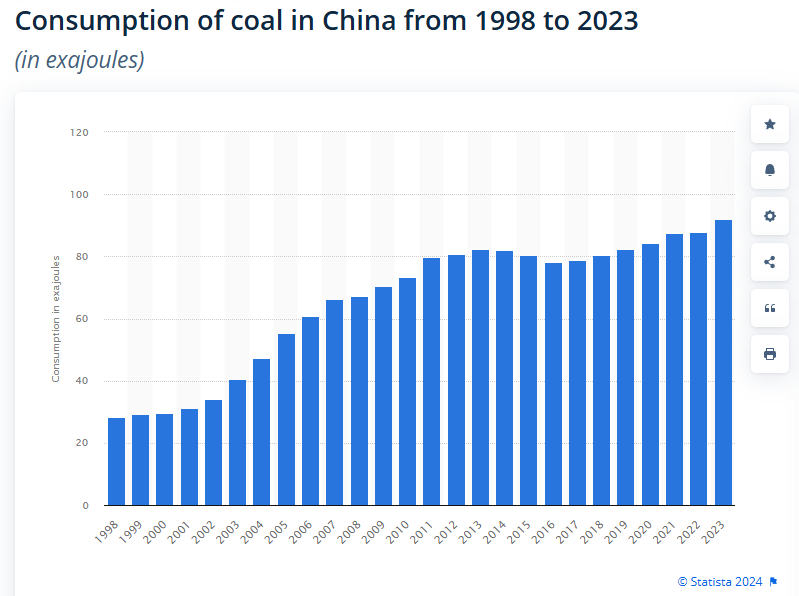

For a start, this isn’t the first time we’ve been here. Some of the very first articles I edited in China were celebrating China’s supposed ‘coal peak’ of 2013.

“We argue that China’s coal consumption has indeed reached an inflection point much sooner than expected, and will decline henceforth,” ran a 2016 article in Nature Geoscience, which all state media gladly reproduced — here, here, here, and here.

"It is not important whether the peak year was in 2013 or 2014, what matters is the reversal in the trend," the article crowed.

In actual fact, 2016 was a reversal — only it was back upwards. Today, consumption is higher than ever. And climbing.

So, why were analysts so wrong? What did people miss…?

“Events, dear boy, events”

First, there’s the words of the big man himself.

Speaking via video link to the Leaders Summit in April 2021, President Xi Jinping promised: "We will strictly limit the increase in coal consumption over the 14th five-year plan period (2021-2025) and phase it down in the 15th five-year plan period (2026-2030)."

This fits China’s wider promises to peak its overall CO2 emissions by 2030, and to make the country "carbon neutral" by 2060.

In this five year window, the CPC has given itself plenty of political wiggle-room, to accommodate external factors — and boy, have there been some of those.

First. Russia.

When China’s “no limits” partner lurched into the Ukraine invasion, Beijing was there with support (—still ongoing, see last story).

In 2022, when the rest of the world was hitting Russia with sanctions, China went the other way, and removed tariffs on Russian coal. That year, trade increased by 20%, and by 50% in 2023. This jump was also replicated via the proxy country of Mongolia.

Only when western nations grew wise to this evasion, and threatened sanctions against China itself, and only when China’s domestic coal producers struggle to compete with this cheap influx, did China put the tariffs back on, and trade collapse.

China is working through these cheap coal stocks now.

“Black mountains are gold”

Then there’s the economy. It’s no secret that some puff has gone from the Chinese growth dragon.

Even officials and top economists are beginning to admit it. So much so, the securities regulator says analysts should be fired if they don’t "play a positive role in interpreting government policies and boost investor confidence".

And coal is a massive part of China’s economy. In 2018, the coal sector accounted for 46 percent of all Shanxi’s tax revenues.

“Green mountains are gold mountains” runs the much printed Xi Jinping quote. He could easily have said “Black mountains”.

When the economy dips, coal can prove a good short-term way to boost growth. One study found that 1 percent increase in coal consumption in China equals a 0.145 percent of GDP growth.

Coal also employs people. A lot of people. According to one report, each new coal plant brings 7433 jobs to the local economy.

Each plant requires vast logistically chains. To dig it. Transport it. Burn it. Compare that to passive wind turbines, or solar panels. If coal is phased out, over 8 million could lose their jobs — and only a quarter of those will be created by renewable energy.

And yet, even after all this human manpower, thanks to China’s low labour costs, coal still often works cheaper per KwH than wind, or solar.

More important, is where this industry is. Shanxi, like many of the coal regions, is one of China’s poorest provinces, where disposable incomes are barely a third of people living in Shanghai.

What in the West is mostly a question of economics, in China becomes one of social impact.

For a party who rose to power, and stakes its legitimacy on the backs of a rural worker-led revolution, they are obviously hesitant to squeeze the proletariat too hard.

Faced with the choice between domestic unrest, and international climate commitments, the CPC is deliberately putting people over planet.

Is China a role model?

Scan any state media article, or propagandist’s guff online, and you’d be fooled into thinking China is a world leader in the transition to clean energy.

In raw numbers, they are. Like the 5GW solar farm in Xinjiang — the size of New York, and could power Luxembourg. Or that China supplies 95% of the EU’s solar panels.

Growth too. In 2023, China added two times more wind and solar capacity than the rest of the world. At this rate, the sector will triple by 2030.

Yet, it’s worth pausing to assess how far, and how quickly, most of the world has quietly come, and with much less state-media backed self-congratulation.

Take my native UK, famous for its coal-powered London smog of 1952, which killed 12,000 people. This year, Britain shuttered its last coal power station, and there are increasing number of hours when the country is powered solely by renewables. In December, high winds meant supply outstripped demand so-much-so, that wholesale energy prices went negative. Wind farms were paying consumers to take their power.

Sound good? Actually, the UK is distinctly average, ranked just 86th in the world.

Five countries are now 100 percent renewable energy-powered, and 12 more than 98 percent. China isn’t one of them.

This year, the EU generated more power from renewable energy than fossil fuels for the first time, something China isn’t predicted to do until 2045.

In fact, China, who Xinhua writes is a “China a leader in global energy transition” whose made “remarkable contributions“, ranks just 96th for its renewable energy mix, well below the world average.

One argument oft made, is that as a developing nation, China should be given leeway to meet its climate goals.

Yet look closer: Lesotho, Nepal, D.R. Congo, Ethiopia and Namibia are in the top 12, all with more than 98% of their power coming from renewable energy.

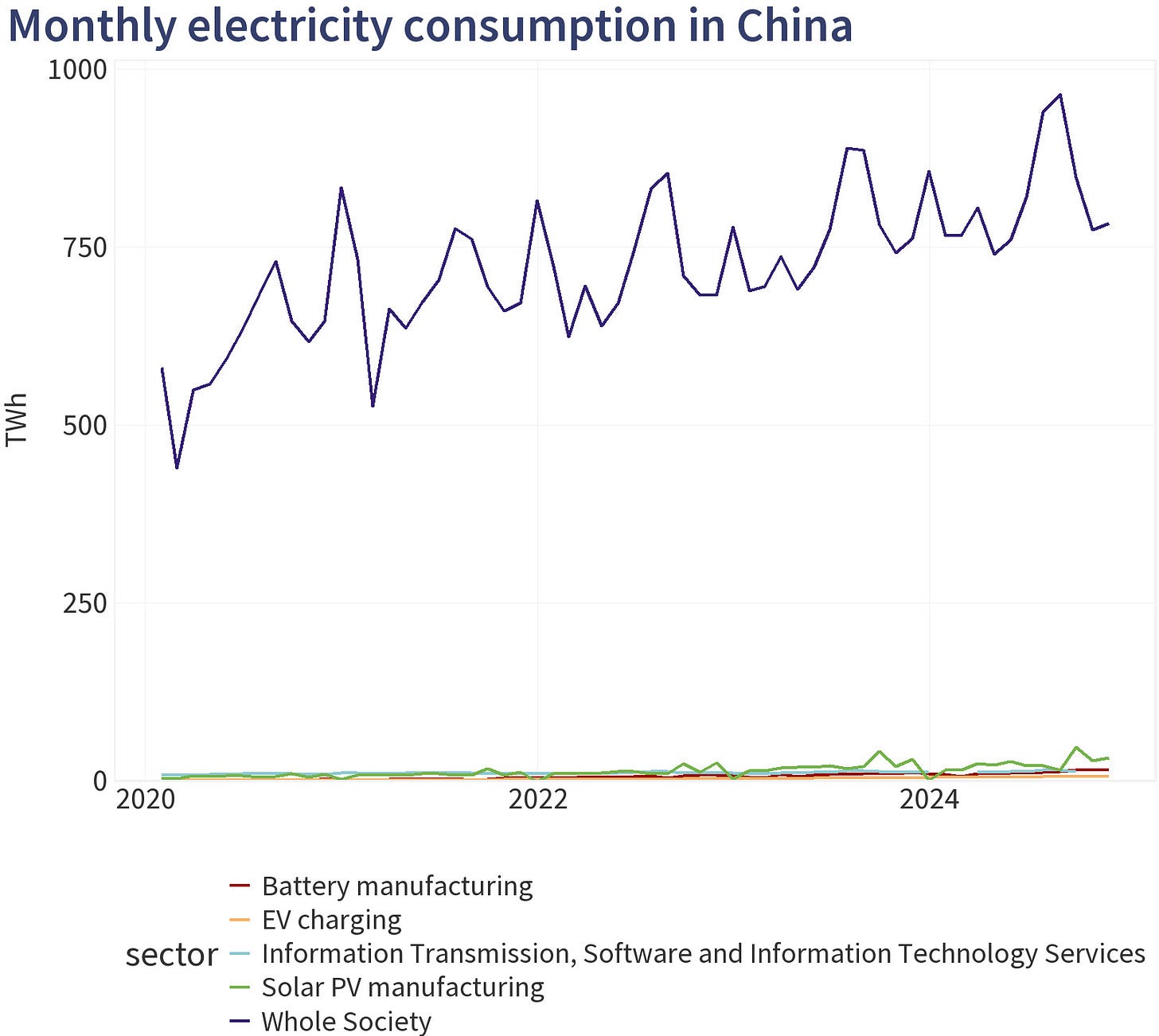

Another argument is that this dirty coal growth is being used to power a clean future, filled with data centers, electric vehicles, or solar panel production — that, too, is a misconception.

According to analyst Lauri Myllyvirta, these nascent futuristic industries make up just a tiny part of China’s electricity demand, with “IT services accounting for 2% of electricity-demand growth.”

Up to ten times more, he estimates, comes from people switching on their new air conditioning/heaters.

‘Coal: the big dirty secret’

Despite this article ostensibly being about coal, I’ve deliberately not mentioned the size of China’s sector until now. That’s because, in many ways, it’s the Party’s biggest, dirtiest secret.

In 2023, China burned more coal than the rest of the world combined — 56 percent to be precise.

Even using the substitution method (which inflates the impact of renewable energy — nerdy explanation: here) it’s hard to miss the sheer scale of China’s reliance on the black stuff.

Even by this measure, China’s fossil fuels outstrip renewables 5:1.

Remember, that fact of China’s solar and wind tripling by 2030?

Such is the sheer size of China’s coal industry, all that new capacity is the equivalent of coal sector growing by just 3.4 percent annually. And in 2023, China’s coal demand grew by 4.9 percent.

It’s not just the CO2 released while burning coal: the mere act of digging it out releases around 10 metric tons of methane annually — a gas 28 times more impactful to global warming. Here, China out-pollutes the whole world at more than 2:1.

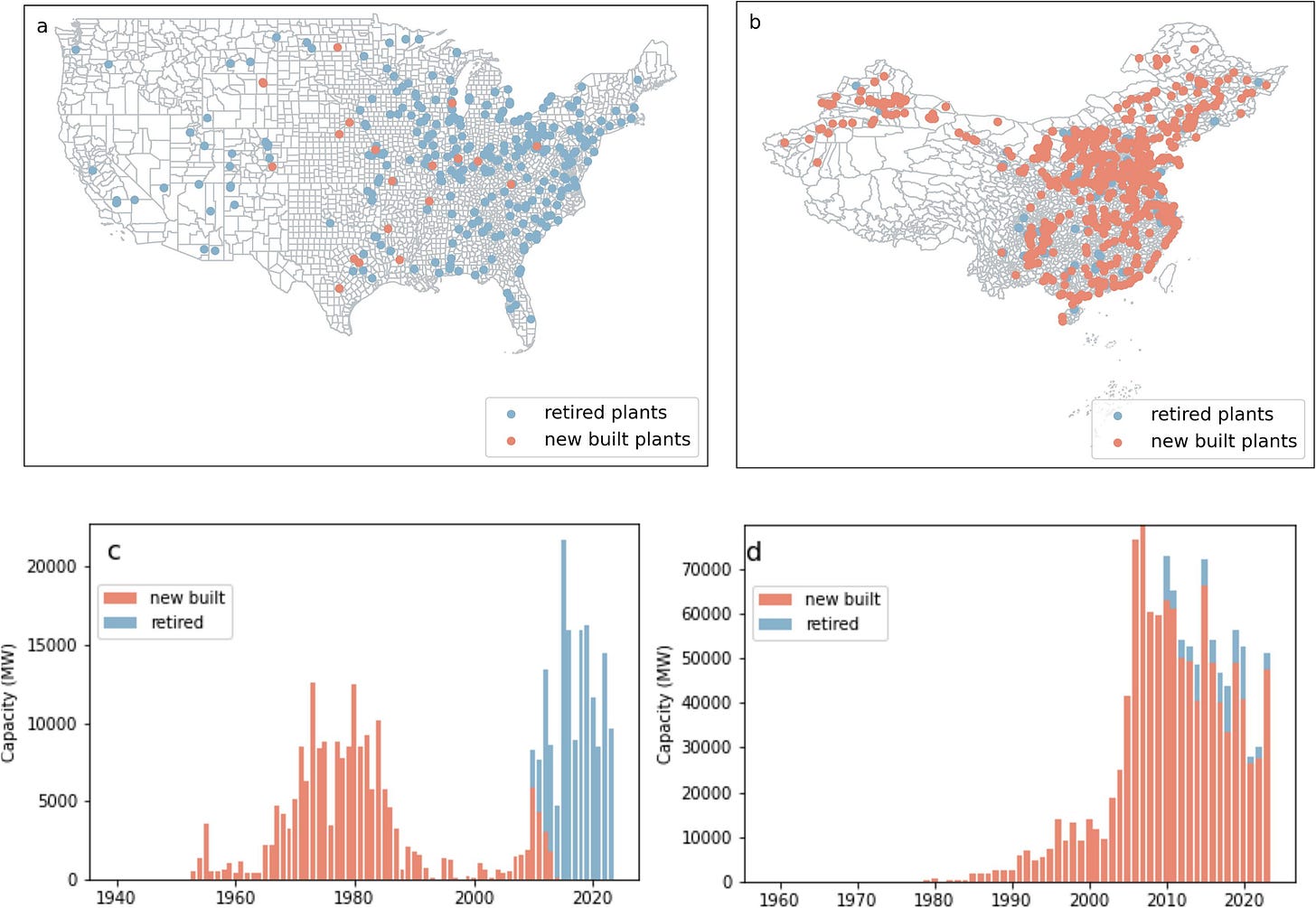

There’s another fact China likes to hush up: just how new this industry is.

In the US, just 10 percent of coal plants are less than 20 years old: in China, 90 percent are.

In 2023, 95 percent of all the world’s new coal power stations were built in China.

Some of these new plants are truly massive too. Take the 3 billion yuan 700 MW Yulin Yusheng coal power station. When finished, it will be big enough to power up to half a million homes.

A fact that can’t be ignored, is China committed to coal in spite of the scientific evidence. In 2006, the year Al Gore won an Oscar for ‘An Inconvenient' Truth’, China greenlit a record amount of coal power stations.

China argues it needed these plants to power its explosive GDP growth, urbanisation, and manufacturing ascendence, and that poverty alleviation takes precedence — yet it didn’t have to.

Aside from only China and India, Brazil added the most amount of power generation in the world from 2015 to 2023. It “met this entirely with wind, hydro, solar and bioenergy, in that order, with fossil power falling,” notes Lauri.

To excuse this uncomfortable truth, many Chinese state media outlets like to talk of historical contributions. They’re less keen to talk about the present, and for good reason.

Here’s why: since 2015, China has been responsible for 90 percent of the world’s emissions increase. Ninety. Percent.

Mostly, this is to do with the sheer size of the country, 1.4 billion people — a fifth of the world’s population.

To circumvent this, propagandists tend to talk in terms of “per capita” as a fairer measure. Note how when they do though, they usually show outdated charts like state media’s Jason Smith sharing this one, from 2019, in 2023. That’s also for good reason.

In 2023, China overtook Germany and Japan, two fellow manufacturing hubs, as a bigger emitter of CO2 per capita.

Another line pursued is: “China is the ‘factory of the world”, and the West has exported its emissions to China. This is also true. Yet, to a point.

In 2022, Germany produced twice the number of vehicles per head as China, while Japan produced almost 3 times more than China. Finland has a heavily industry-focused economy (steel, chemicals, logging), yet produces a quarter less CO2 per head, and falling.

Needless to say, with China being the size it is, all these emissions add up. China now emits twice as much CO2 as the next closest country (the United States). Viewed graphically, its recent growth is vertical.

More worrying, this growth isn’t slowing ay time soon.

At the 2016 Paris Agreement, the EU agreed to cut their emissions by 40 percent. Since then, China’s has gone up by a quarter. And they’ve promised it won’t stop climbing until 2030.

At the current rate, by 2037, China will have emitted more CO2 than any other nation, in all human history — impressive, considering its late start.

These are the stakes. And why ‘peak coal’ matters.

I’ve long been a climate change optimist: humans when pushed into a corner, tend to innovate their way out of it. China has been at the forefront of that. Via batteries, EVs and solar panels.

There’s even a little eco-method to some of these new coal plants. That massive 700MW Yusheng power station? It’s to replace 702 MW of smaller, more inefficient plants in the area.

But that isn’t to give the country a free pass, or much less, the adulation that the state so constantly seeks.

Consensus says coal will now peak in China between 2025 (Sinopec) to “before 2027” (the IEA), though even this hangs in the balance. While H1 2024 saw just 9 GW of new coal permits greenlit — an 83 percent cut — the Government plans to bring 80 GW online in 2024. If so, that would be another near-historical record. Another step further from meeting their goal.

So, why?

The wider fact is the CPC has a very set hierarchy of needs: Party consolidation of power first. Lifting of the people, second. Self-sufficiency, third. And wider objetctives, fourth.

Climate falls into the latter.

Coal is cheap, easy, and satisfies more pressing aims.

I don’t doubt the CPC’s long-term commitment to a green economy — you don’t become the world’s largest renewables supplier without huge political buy-in.

But it’s not at the cost of pragmatism. Cheap coal, a chance to improve ties with Russia, and trusted ways to boost poor provincial economies have been too good to pass up.

The leadership has given itself political leeway until 2030. Why self-sacrifice before then?

Chinese coal consumption in the power sector DID drop over the first half the year as renewables performed well. It only rose in the second half after hydropower production faltered later in the year. Of course I don't like being wrong with my prediction in the end, but I don't think it was a bad call at the time. I caveated those predictions several times throughout the year by adding "assuming hydropower performance remains strong" and so I'm not particularly surprised that once hydropower indeed slipped, coal had to fill in. A bummer, but I'm not losing sleep over it.

The silver lining is I was incorrect in my production in TWO ways: I assumed that if the power sector failed to peak emissions, then the entire economy would fail to peak emissions; this may not be so clear cut after all, since declining emissions in heavy industry may have made up the gap. That's more Lauri's space than mine, but he was pretty bullish at the end of Q3 that we were on track for a whole-of-economy emissions decline in 2024 and I have no reason to doubt him. We'll see once the whole year gets counted.

Of course, the deadline is 2030, and so I doubt we'd see any strong change between 2025 and 2030 (a plateau most likely) unless market actors again exceed expectations, like they did in 2022-2023. The profit-seeking behavior of market actors (not government mandate, or some deep well of Xi Jinping's green energy convictions) has been the key driver of most renewables projects. I wouldn't look for evidence among government actors and regulators to figure out whether coal or carbon peaks early - I'd look for the evidence that companies (both SOEs and private sector) see a pathway to profitability by building renewables, and that such an environment has been created for them, letting the market do its thing. That's clearly happening - hence my optimism.

As for your swipe at my character - I see my block on Twitter is quite justified...I feel you practice a kind of public persona cultivation based around smug quips and clashing with other public commentarians to raise your own profile, and if you want to be seen as that kind of China Whisperer, that's your business, but I find it very abrasive. The people I want to spend time interacting with (or "my people" as I describe in the thread you helpfully linked) are shorter on the *wink wink nudge nudge* "well we all know how cHiNa is" quips, shorter on the smugness, shorter on the complaining, and much longer on the expertise. Take care, and happy new year.

I think the mistake state media often makes is that even when China makes progress, it leaves out obvious context that might work if Chinese media is your sole source of information, but for anyone outside China, it doesn’t. The graph you included shows that while coal remains the dominant energy source, its proportion relative to other energy sources has started to plateau, and its overall dominance in the energy mix is declining.

It’s rare to hear state media openly acknowledge that China is still so heavily reliant on coal. But if it highlighted the progress China is making in renewables while also providing context for its continued reliance on fossil fuels, I think viewers might actually feel more inclined to celebrate China’s achievements in this area.

Also, just want to add that even if I don’t always agree, I do find David’s takes on social media consistently thought-provoking. I interviewed him once for a news segment—he’s a really top bloke. Just my two cents worth. Great read, as always.