How Chinese state media are quietly targeting "elites" via Substack

Journalists say they are writing "independent" newsletters. Their employers say otherwise.

This is part of a wider look at “Media Studios”. How Chinese state media are attempting to influence international audiences via supposedly arms-length media professionals. This week: Substack.

Chinese state media have identified Substack newsletters as a potential way to target and sway Western “elites”, according to a series of recent industry articles.

More, in celebrating their success, the state media posts have unwittingly outed several Chinese-journalist-led Substacks that claim to be “independent”.

“In recent years, domestic media organizations have begun exploring the use of newsletters for targeted communication, achieving considerable success in influencing key audiences and serving as a "light cavalry" force in international communications,” states an article in China Journalist, a periodical aimed at state media industry professionals.

Substack taps into a current disillusionment with mass media, and allows to authors speak directly to readers, the article notes. For Chinese state media — which have regularly been blocked, labelled, or throttled on international platforms, that brings extra potential.

Substack allows the state to “bypass algorithms” and “effectively target information at specific audiences”, writes Du Jian, Deputy Director of the External Communication Office of the Xinhua News Agency’s International Department.

“Compared to other media, newsletters are a long-term, silent way of doing things,” he adds.

Xinhua is one of many top level Chinese state media which have attempted to grow audiences on Substack, to mixed success.

The trick, Du says, is to establish a “benign mutual relationship” with a “few key” thought leaders. From there, the state can then “influence readers’ thoughts drop-by-drop” on key issues, attempting to “establish a correct understanding of China”.

“This is my personal opinion”

Sometimes, part of a Substack’s success comes from disguising exactly who the author is, and obscuring just how much of the content is state-supported.

Among the more egregious but popular examples is Li Jingjing, a reporter for CGTN. Videos like this interview with Neil Bush (George H.W. Bush’s son) was filmed by CGTN, broadcast on CGTN, is hosted on the CGTN website — yet is miraculously stripped of all corporate branding on her Substack.

I’m just “a Chinese journalist. Presenting analysis of world news, non-Western perspective,” her Substack bio states.

However, while Li is bombastic, easy to spot, others are more subtle, and aiming for a more cerebral crowd.

In the Beijing Channel’s Substack’s bio, Yang Liu writes: “I’d like to disclose that I am a journalist with Xinhua News Agency since 2011.”

A few words later, Yang adds: “To be clear, everything I say in this newsletter only represent my personal opinion, not that of Xinhua.”

His employer, however, disagrees.

“Xinhua News Agency's International Department, capitalizing on the demand for high-quality China-related content among influential figures, launched the "Beijing Channel" newsletter.”

The article goes on to note that the “Beijing Channel” is followed by over 4000 subscribers including (bombastically) “all diplomats stationed inside China, foreign media reporters, and scholars”.

Yang isn’t the only one caught out by the state’s chronic need to self-congratulate itself.

Capture Substack’s “elite subscribers”

Jiang Jiang (姜江) is one of the most followed (13k) and respected writers talking about China on Substack today, thanks to his long-running newsletters Ginger River Review and Beijing Scroll. The content is dense, wonky. According to marketing, “it currently has the largest overseas subscriber base and the fastest and most stable growth among all newsletters of Chinese media professionals.”

In both the newsletters’ ‘About Me’ pages and his personal bio, Jiang Jiang is upfront about his employer, but also keen to point out his supposed editorial independence.

“The analyses presented in this newsletter reflect my personal views, not those of Xinhua,” he writes on one. “Views not representing Xinhua,” on another.

Only, again, this isn’t entirely how Xinhua sees things.

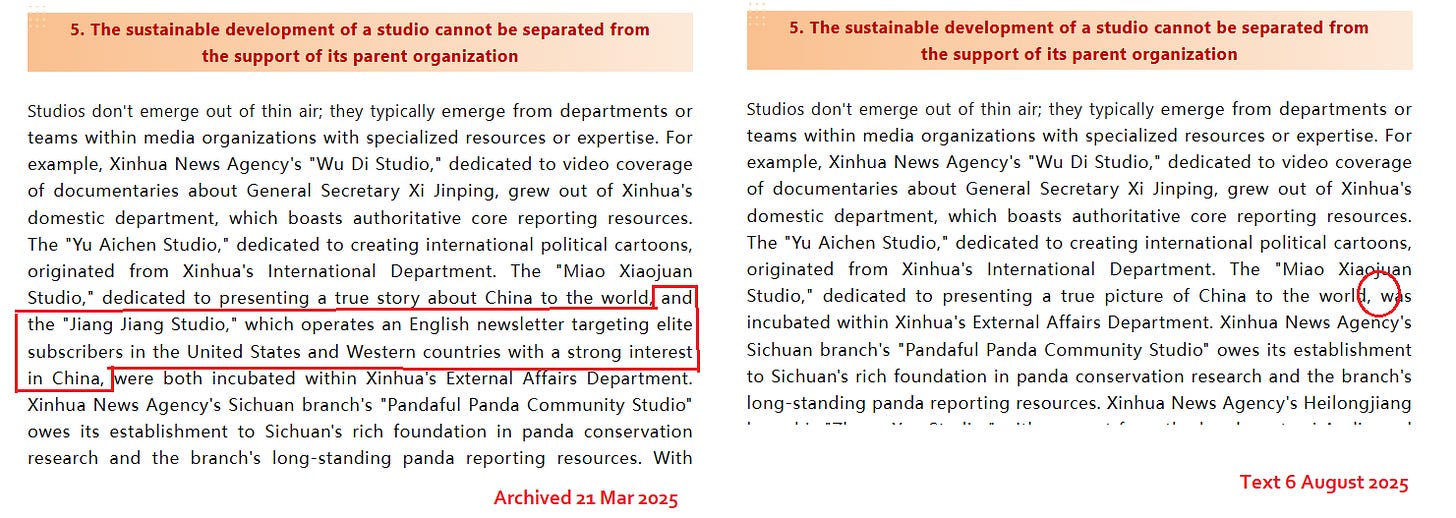

In a recent article, celebrating its media studios, Xinhua lists Jiang Jiang — and his newsletters specifically — as one of its key successes.

“The "Jiang Jiang Studio", which operates English newsletters with elite subscribers in the United States and the West as the main target audience, is hatched from the external department of Xinhua News Agency,” the article emphatically states.

Perhaps too emphatically. At some point in the last few months, this sentence has been deleted online.

Later, the article later explains how views are moderated — a practice completely at odds to the “independent” ethos Jiang Jiang portrays.

“In terms of security management, the Internet celebrity studio accounts are included in the security management and assessment and evaluation system of the whole agency's editing business, and the news review and release process is strictly enforced.”

Xinhua further explains how it supports Jiang Jiang and its other studios economically, and via ‘political training’.

“We tilt human, financial and material resources towards the studio, provide it with venues, equipment and financial support, and hold training related to the studio's business many times to improve the political literacy.”

Examples of these venues can be seen in a recent upload of the JJ’s Got China Podcast, tagged as “Quality video content on China, sponsored by Xinhua Institute”.

“I know this is not our usual setup,” the hosts open, away from their typical studio. Where is it filmed? They don’t say, but I recognise those mildew-coloured walls, and dank chairs.

“Strengthen coordination”

State media in China is a strange biome, where organisations are both in competition with one and another, and also expected to share their learning.

External propaganda should “strengthen the strategic coordination among institutions and departments,” Du writes.

Partly this is through journals, industry awards, study sessions, visits — but more evidence, again, can be seen with Jiang Jiang.

Last May, in event jointly organised with the Center for Strategic and Security Studies, Jiang Jiang delivered a two hour lecture at Tsinghua University, in Beijing on “How to Tell China's Story Well Through Newsletters”.

Previous lecturers in the series have included Liu Xiaoming, former ambassador to the UK, who once famously told China’s story so well live on the BBC, he was fired shortly after.

More than 30 students attended the session, and a roundup notes they: “enthusiastically asked Jiang Jiang questions about how the newsletter helped disseminate China's policies.”

Incidentally, Jiang Jiang was also a guest at an event in January 2024, hosted by the think tank Center for China and Globalization, and featuring a delegation from the British Foreign Office. Topics included “how to enhance mutual understanding through newsletters”.

On signup to his Substack, users are automatically enrolled into following 44 other accounts, which provides a venerable “who’s who” of state media accounts.

These include You Zhixin who runs the Substack Shanghai Miscellanea and describes herself simply as “a journalist in Shanghai”. Unmentioned, is that she’s also of Xinhua.

Yingshi “Fred” Gao, who writes Inside China, he’s CGTN.

Einar Tangen of Asia Narratives, described as a senior fellow of CCG — and also of CGTN.

And so, on and so on. Others are more dubious, such as Mario Cavolo, a US-born pasta sauce maker in Dongbei, once a regular talking head on state media, and a fellow at CCG, until his increasingly deranged social media posts saw him mostly taken out of rotation.

As Deng Xiaoping used to say: lift all boats?

“single soldier combat”

Is this push working? Well. State media believe so.

“Influence is increasing”, Du notes in his article last November — and that was pre-Substack’s recent influx of new users.

While nearly all state media posts on Substack attract little-to-no engagement (there’s dozens of accounts not mentioned here, very few register double digit engagement), sometimes content does break through to wider audiences.

One post by Xinhua’s Beijing Channel, a translation of an Elon Musk article for China Cyberspace, commented on by Elon himself, hit over a million views when it was shared again on X.

State media are even using the attention of old Substack doyens as yardsticks for success. In one write-up, Xinhua boasts:

Bill Bishop, a leading Substack influencer with 100,000 followers, not only quoted the report "China's Path to Modernization," but also shared a link to the full text. This move further expanded the influence of the Xinhua think tank report and its brand image among key audiences and opinion leaders overseas.

There are problems. Du notes Chinese Substacks started much later than their Western counterparts, adding: “Most of them are single soldier combat, lack co-ordination, and have not yet achieved scale nor momentum.”

The biggest challenge, however, is left completely unsaid.

State media are trapped. They know they have a trust issue. They know everything they ever produce will carry a heavy asterisk — “Party Endorsed”. Hence the temptation to obfuscate their roots.

However, Substack is a tight, learned community, where audiences are built on trust. Word-of-mouth travels fast. Attempts to camouflage might prove tricky.

I think there was a time when state media journalists could independently run newsletters. A couple of specific individuals come to mind. I had a newsletter (the platform was Revue, X killed it, and unfortunately I did not get a chance to archive my posts) back in the day, and I used it to share my work and fill in the gaps with information left out of what was broadcast. I didn’t ask for permission to do that, and was never asked about it. This was years and years ago. There were a couple of other people doing something similar — but the sad thing about state media is that it takes anything that grows organically, providing some additional context and building a genuine following, and tries to whitewash it, reproduce it on a mass scale, and force those who went with the “ask for forgiveness, not permission” route to either continue but only with approved messaging, or stop. The same happened with WeChat official accounts back in the day, and then Facebook, YouTube, X…

I understand why Chinese state media is trying to go where the audience is, but those imposing restrictions & censorship still just don’t understand that the only way you will ever engage an audience is not by force-feeding them sanitised state media talking points, but through authentic, organic, and genuine content that has a purpose other than acting as PR for the CPC and China.

A well-researched essay like yours needs a well-researched response

https://www.china-translated.com/p/my-experience-of-working-with-a-substack