The other China: Life in a rural village

I spend a few days in a rapidly vanishing place. Where food is free, doors are left open, and the main currency is grandchildren.

To be fair, the car had done well — 500 kilometres of driving itself. Only when the road ran out, when asphalt turned to ribbed concrete, when motorbikes veered round corners on the wrong side of the road, and chickens roamed, did the autonomous driving start to get confused.

I was heading to the most rural, of rural Guangdong. Tucked away in the hills, right on the border with Guangxi. It’s about as far as you can get from Shenzhen’s gleaming towers, air-conditioned shopping malls and robotics industry without crossing borders, or falling into a different century.

I’d read that with its snakes, spiders, mosquitoes, and thickets, historically, this was once an area where errant Beijing nobles were banished to, for a fate worse than death.

“No… there’s no snakes,” Nainai laughs.

Later, I see a dead many-banded krait laying on the road. The world’s seventh-most poisonous snake, this baby specimen could bring down an elephant.

“Oh yes. We have that one,” she later tells me, back at the house. “We call that a ‘bad snake’.”

I’ve come to see my Chinese grandmother, Nainai. A lady of 90. Face of dark skin and many wrinkles. She walks with a near-right angle stoop. But even stood straight, she would barely reach my chest. She’s Hakka, as are everyone round here. Officially, they’re not a minority — they’ve contributed far too much to China’s story to be hived out from the Han majority. But drop a Mandarin speaker into these valleys, and they’d struggle to talk their way out.

I never, ever mention my family, partly because I don’t want to be yet another foreigner extracting exoticism through his marriage, but mostly because they’re not my stories to tell. But on this occasion, I’ve got special dispension. Not many outsiders get to see this side of China — Chinese included.

I sit on a tiny chair, its seat barely off the ground. My knees come to my ears.

“Has there ever been a foreigner round here?” I ask.

The locals put their heads together. A few minutes of animated conversation. Then the verdict: “Yes. A black man went to a nearby village, once, about fifteen years ago.”

I make a mental note to be on my best behaviour. Long memories. For God’s sake, don’t cause a scene.

On arriving, I do my usual and say hello to Nainai’s chickens. Each morning, she scrabbles down a slope to feed them. They’re fat and glossy.

Moment’s later, I meet one on the dinner table.

Meals are simple. Meat. Rice. Vegetables. All the ingredients are fresh, as the chicken head staring at me reminds me. I feel a pang of sadness, a sudden urge to convert to vegetarianism, until I try a bite. This is not like any chicken I’ve had before. It’s actually has taste; hulking muscle to gnaw on. It’s ruined chicken for me. All others now taste like tofu.

They introduce the dishes. Chicken, boiled using a wood stove. River shrimp. Some dark green leaves. And for flavour, sha jiang — a type of wild green ginger, with a tangy taste, that I discover I love. As I’m dipping in, they tell me the kicker: everything on the table was grown, raised, caught or foraged for free.

“Do you want to see the farm?” asks an aunt, who’s both a neighbour and Nainai’s helpful hand.

Yes. Yes I do.

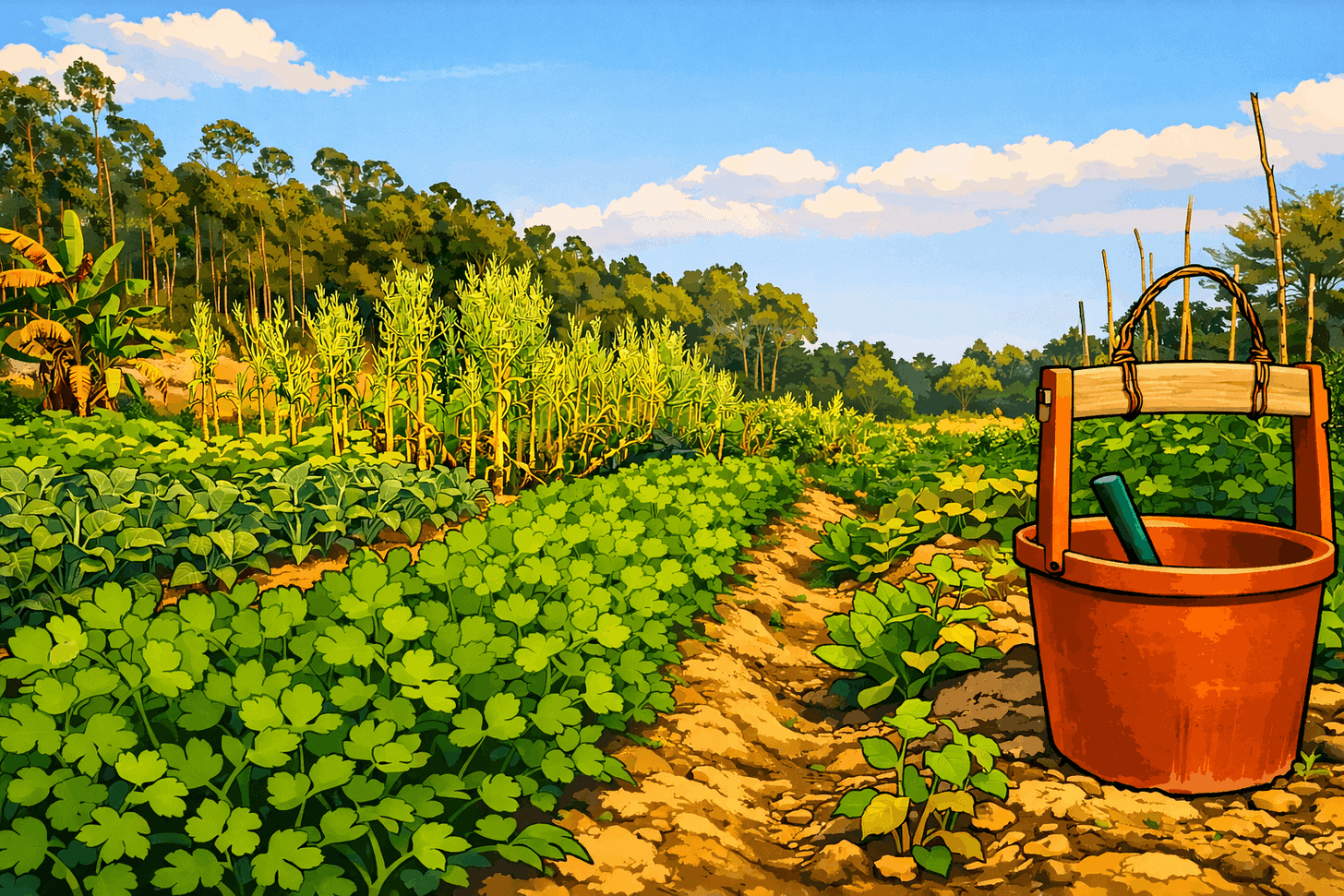

Farming

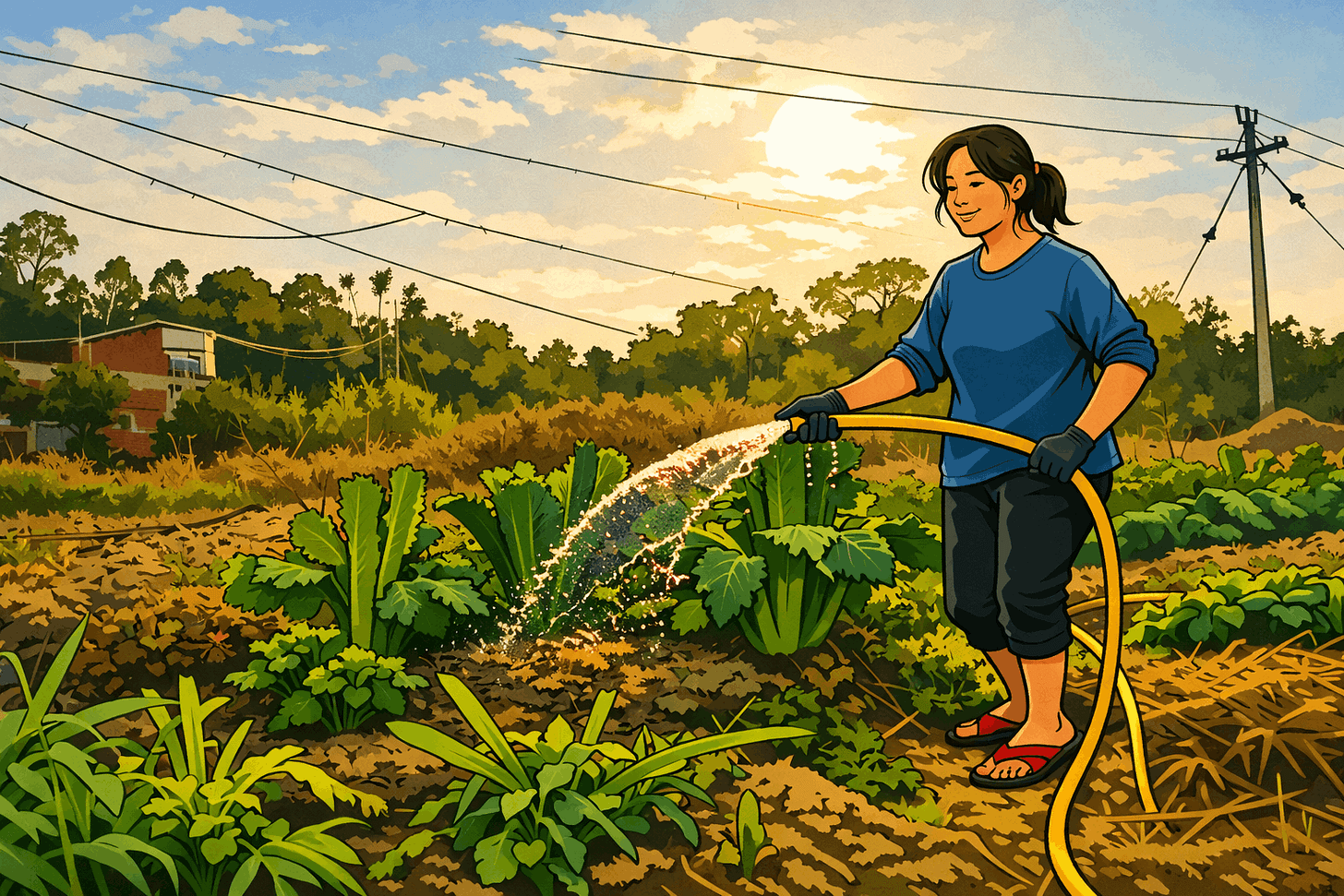

“Do I look like an old propaganda poster?” she asks, as I take her picture. She does.

“No one was using it, so I thought I might as well.”

By hand, I see she’s hacked out four mu (2600 square meters) of riverbank oasis. A mountain of green. Bananas, cabbages, sugar cane, beans, peas, pak choi, lettuce, tarot, chives, coriander.

Guangdong is subtropical, so it gets two harvests. In Winter, when the sun is softer and the insects are gone, the field is vegetables. Then in Summer, she dams the river, flooding the field, allowing a second harvest of rice — 1.5 tons of it. A third of food is kept back for family, friends and neighbours, the rest is sold at around ¥2.2 per jin — around $630 total.

Not much is wasted. The rice husks are shredded up and used to fatten the foul. While mulch goes back into the soil.

There’s very few expenses. Ploughing is hired in. The tractor costs ¥150 per mu. “It only takes him a few minutes,” she says, shaking her head, as if she’s being ripped off.

No fertilisers. Each year, the field is burnt back to rejuvenate the soil. Insects are simply washed off. And if they need it, plants get a sprinkling of ash.

For a country swamped by creepy crawlies, that sings with a din of cicadas at night, these pristine leaves are an incredible feat. I remember my sorry-looking kale back home. Gaping holes gnawed out. I probably won’t burn off the garden — the British fire brigade tend to take a dim view on that. But the slugs are definitely getting a face full of ash, next time I see them.

I stare round. “How long does all this take?” I ask. Her answer shocks me.

“Maybe… an hour a day?”

I watch her watering the plants under a setting sun. And I think of city life, of sweaty commutes, and long hours sucking up to inept bosses.

What the hell are we doing.

Now, I haven’t mentioned what the homes look like yet. Perhaps, you’re picturing something out of an old National Geographic, a brick shanty, perhaps, or a grass hut from a Vietnam war flick. You’d be wrong. The house has five floors. As do many in the village. Its a mini-Manhattan, concrete and glass, rising up from rice paddies.

Custom is to build a floor for each branch of the family. Come Spring Festival everyone bundles back, to celebrate with the eldest. Showboating comes into it, too. If the neighbour has three floors, of course you’re going to have four.

Unlike the rest of China I’ve seen on this trip, where there’s been a noticeable drop in cranes since I left four years ago, I note that, here, construction is still non-stop. I pass numerous houses — nay, mansions — going up. I point out an ostentatious one: “How much for something like that?”

“Maybe 10 wan in labour? Same for materials?” That’s $30,000. Some spend more. Yet most spend a fraction. This is partly how China has 90 percent home ownership.

Land is free. Technically, all ground in China is owned by the state. Yet, out here, if you want space, you simply look for an open spot, mark out some boundaries. An official comes by, and if no one complains, it’s yours.

I quickly learn that life in the county is dominated by one phrase, so ubiquitous, it might as well be printed on the all the town signs: “The mountains are high, and the emperor is far away” (山高皇帝远).

It’s not lawlessness. Rules are followed, unless they are stupid. In which case, they are promptly ignored.

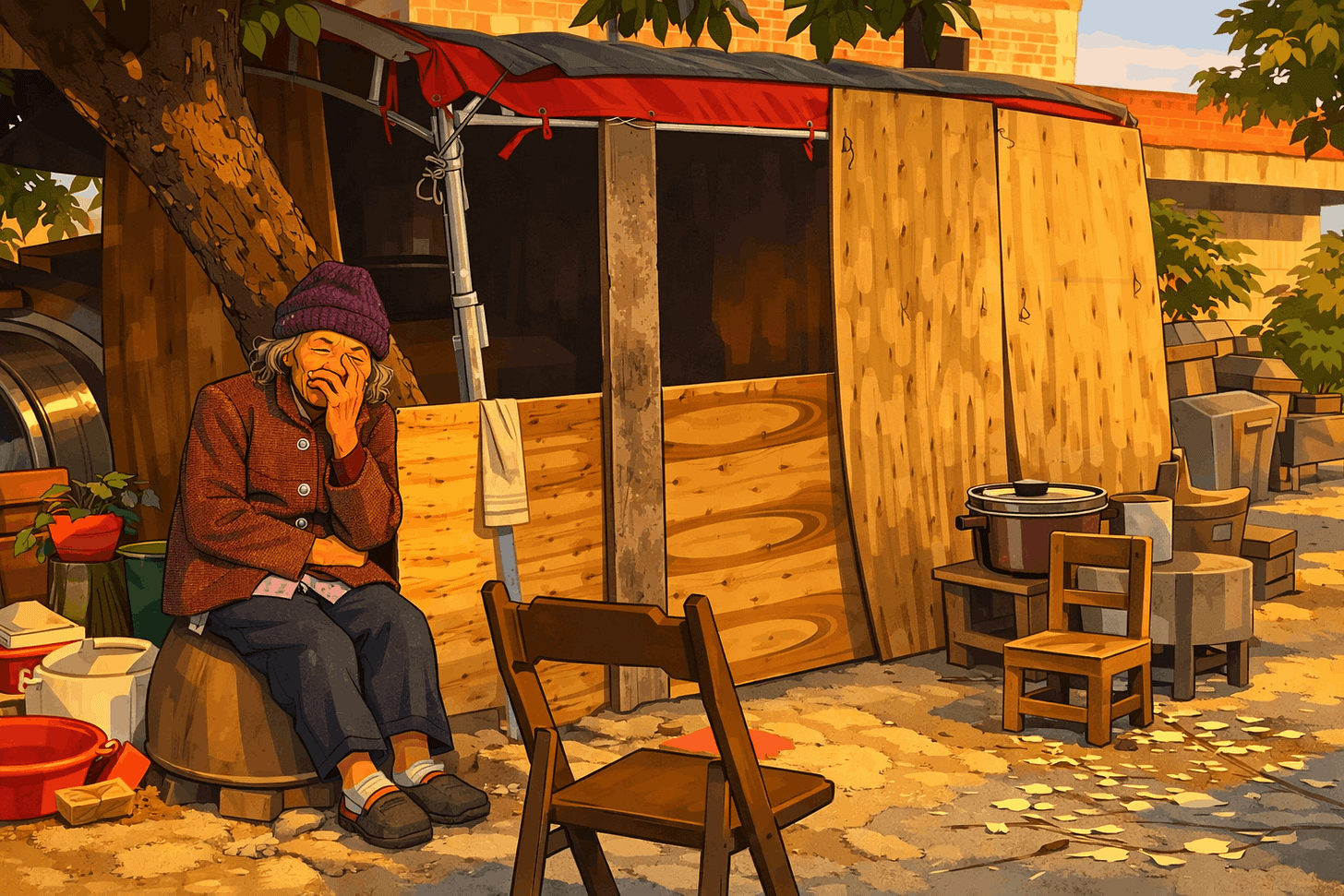

It isn’t all grandeur. Most homes, even the sparkling ones, are bare inside. Others make do with something even more humble.

On arriving, we divide fruit as gifts and go looking for old familiar faces. There’s one old lady in particular I want to meet. In 2021, when the CPC declared a “total victory” in eradicating extreme poverty, she was the first person I thought of.

Her house is mostly scavenged. Not unusual. Out here, I see many more shanties. She has family, and is known to the local Party, but to save face, Beijing pretends she doesn’t exist. She’s a statistical anomaly.

When we find her, it’s late though, and she’s already sleeping. I see she’s retreated back to the brick part of her home, a single room, akin to a sty, not much bigger than her makeshift bed. Well into her 90’s, she seldom comes out now.

Village life isn’t exactly private. Yards are interconnected. Doors are left open all day. People wander in for meals, and tea.

We’re talking outside, when a 95-year-old man shuffles past. Partly deaf and mostly blind. He sees us, and shuffles over. “My bed is broken, but a man has fixed it,” he opens with. He’s a raconteur, speaking non-stop, lurching through topics: broken bed, lychee trees, neighbours.

Suddenly, he pauses, shuffles up, until he’s nose-to-nose with me, and squints hard. “Wait. You’re not Chinese!” he exclaims.

I prepare myself for a barrage of questions, wait to bask in my local celebrity — but no, he shuffles back, and immediately starts talking about his breakfast instead. When I first came here, I steeled myself for politics. But village life is more prosaic. Instead I’m mostly met with a shrug, and a: “You’re big, reach that.”

Then, he announces: “I have five sons and seven grandchildren, but none of them live with me. I live alone.”

It’s a common refrain. In the village, elders measure success by family. It is both their most intense longing, and equally, their biggest cause of pain. The man’s eldest son didn’t fix his bed: a neighbour did. That’s shameful, it hurts. I suddenly realise this isn’t idle chat, he’s conducting village PR, getting ahead of the story, before it manifests as gossip.

A sad fact is that rural suicide has escalated in recent years. Partly it’s poverty. Partly it’s shame. Elders not wanting to be a burden to their families. Deaths particularly spike just after Spring Festival. When the houses empty. And only the ground floors have life.

This old man seems fine, however. I watch him shuffle away, and despite his blindness, he intuitively hops over an open gutter. I hear him telling the neighbour about his bed.

Five minutes later, I see him pass again, further down the village; between two houses; he’s followed by a line of seven chickens.

The walk

A rooster wakes me at 4:30am on Day 2. Suddenly I don’t feel so benevolent. Crow, crow crow, non-stop, directly outside the window. I shove the pillow into my face, and fantasise about all the different ways to cook a chicken. At seven, I give up, drag on my shoes, sneak out, and go for a walk.

Dawn is breaking and the village is just waking up.

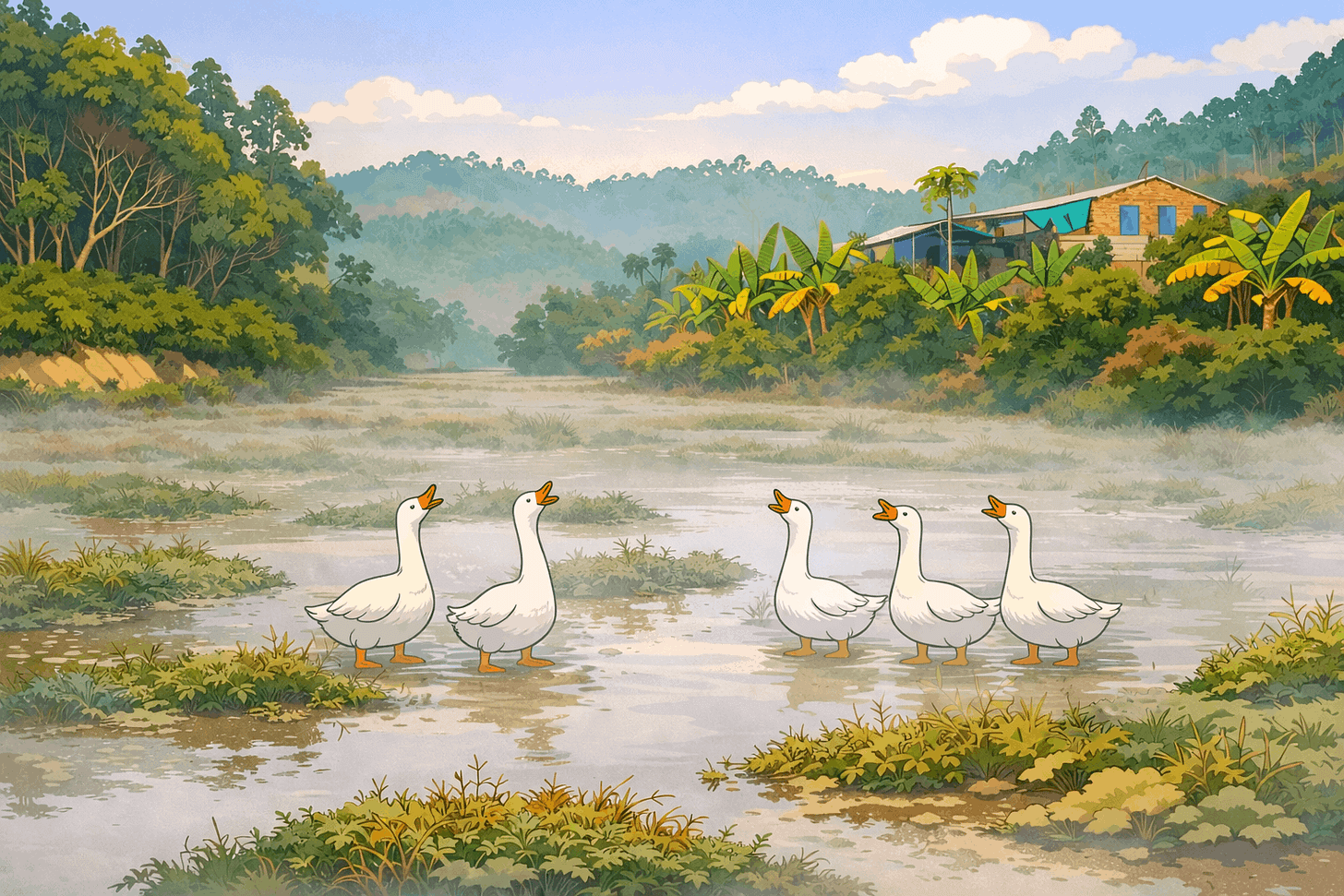

I pass on through, and out into the wild, into a valley. The hillsides are coated in ferns, the valley floor a boggy, swampy grass, covered in mist. In the middle stands a gaggle of wild geese. They stretch their necks and call into the sky. Framed like this, it’s easy to imagine their Jurassic ancestors.

The one-lane road climbs the hillside and crests a corner. At the top, as I pause for breath, and notice a rounded mound of earth, hidden deep in the ferns. It’s a grave. This shouldn’t exist either. Burial has been practically illegal in China since 1997. But traditions, and connection to the land is strong here. So when needed, the males in the family sneak out, under the cover of darkness, to bury their loved ones. I look at the spot, nestled in the ferns, looking back across the valley, watching the sun rise. It was hard to begrudge their rule-breaking. They’d chosen well.

It’s about an hour into the walk when I realise I am utterly, thoroughly, miserably underprepared. The jacket I grabbed was a mistake — it’s 8am and over 20 degrees already, in January. No water. Draining phone battery. And I forgot to pin my set off point. It’s hard to walk in a grand circle when you're not sure where you began.

Luckily, I do have one thing up my sleeve. I realise, thanks to my six words of Hakka, I can form a rudimental conversation with nearly every old lady I pass.

I try it with the first I meet. A little nod, and “Grandma.” She laughs, and walks over all gleeful. She shouts to the house behind. From inside a darkened doorway, a man calls back. I don’t need interpreting. It’s the mating call of every sat man, poked into action: “Urgh… aaand?”

She begins jib-jab-jabbering excitedly at me, arms flapping. And then seems wholly confused when I don’t reply. She tries again. Her brow furrows. Uh oh, time for: Line Number Two.

“Sorry, sorry, grandma… Byebye!”

Stunning success. I try my new technique a half dozen more times, leaving a stream of confused grannies, across the county. Until it fails.

In one village, I’m photographing a house. An old lady across the road, spots me, shuffles over, stares me up and down. She points at the house, presumably tells me they’re not home, and moves swiftly into questions of ‘who are you?’, ‘Why do you know them..?’

“Err, err.”

As the questioning becomes noticeably accusatory, and her big stick starts waving, I make a hasty retreat. Failed. I had one job, keep a low profile. I imagine the headlines across the village gossip network: “Gweilo burglar stopped! ‘I had my stick’, says fearless granny.”

The locale is a mixture of mini valleys, and rounded hills. The valley floors are swampy rice paddies, animals grazing. While the hills are tea plantations, light forestry, and something new: solar panels. From afar, they look like the land has grown black scales. Up close, I see there’s thousands of them, up on stalks, craning to the sun, like dusty flowers. I edge in to a field, but stare at the thick brush round their bases. A good hiding spot for a ‘bad snake’. Maybe not.

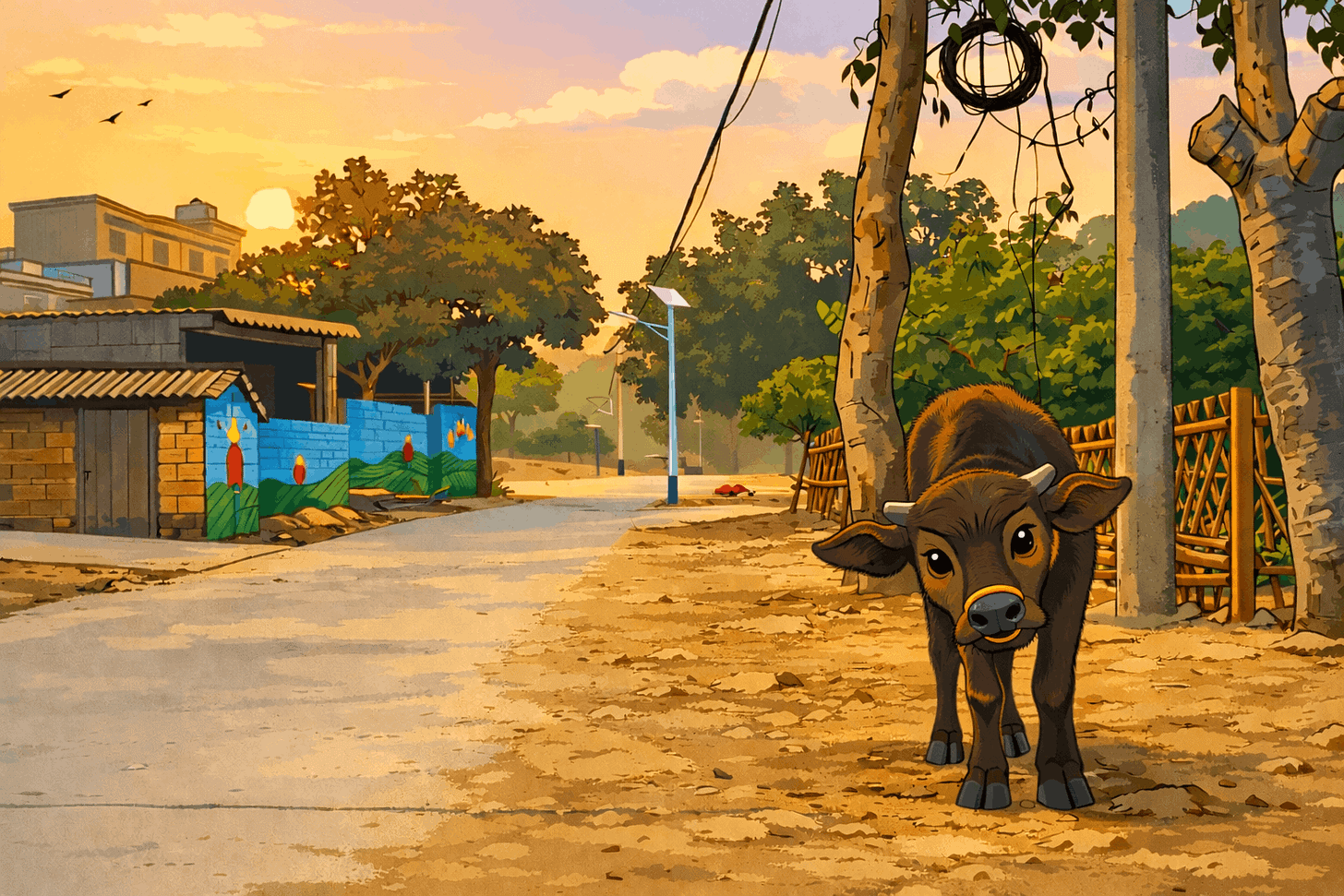

Walking through one village I pass a man sunning himself on his porch. Across the road, a young calf has the opposite idea and is shading itself under a tree.

A couple of hundred meters further, I suddenly hear bellowed shouts from behind. I turn to see the man waving his arms. The calf has followed.

“Gweilo rustler strikes village!”

I try and scare it, but calfy thinks I’m playing. It bows its head to the ground, and skips to the air, twiddling it’s ears. Adorable. I’m never eating steak again.

In the end, I slowly lead it back. Offering as much profuse apologies that my six words of Hakka allows, “beef, sorry, sorry, beef, sorry” — but he’s too busy laughing.

It actually happens again, a few kilometres later. I pass a pig farm, a squealing stink of mess, and a flock of chickens stream out, following me like ducklings. I’m Guangdong’s Pied Piper of farm animals. Only when a guard dog comes bounding out, snapping and snarling, but thankfully yanked back by a secure chain, do the chickens flap back. The dog turns and barks at me. Woof, woof, woof. I’m thoroughly told off.

“Gweilo rustler strikes again!”

After three hours, I’m knackered. The road is wider now and busy. Few cars, but plenty of motorbikes. Lane control seems optional. Left side, right side, who cares: it’s all road.

At one point, a battered old cement mixer screeches to a halt, leaving tyre tracks. Cement sloshes out the back.

I jump into the ditch, look frantically for the thing he has tried to avoid hitting. Chicken? Cow? .. Snake? No, it’s me. I see the driver staring in the side mirror, mouth open, agog. I wave. He smiles, then waves back delighted. The engine roars, and he trundles off.

Returning to the village, I see it’s miraculously grown, again. The road I left down — just three hours earlier — is now a whole meter wider. Seven men sit to the side admiring the fresh cement. It occurs to me, this was probably delivered by the same lorry. (“Road project success! — despite foreign interference”)

In the house, everyone is buzzing at my little adventure. I draw a rough map. They study, and suddenly point at a few villages, laughing.

Apparently, I walked to Guangxi, a whole other province, and didn’t even realise.

I look at where the border is, see a village’s name, and realise something else: I wasn’t just stealing that man’s cow, I was a few meters from smuggling it across provincial lines. That’s a federal crime. I’m dangerous.

Later that night, the local Party official drops by for a few rounds of tea. He’s buzzing to see childhood friends, and eager to talk about his road widening scheme. A true journalist would’ve seized this unexpected access: prodded and poked, asked searching questions.

But I’m exhausted. I shake his hand, and soon leave them all to it.

From upstairs, I hear them telling the story of the mad gweilo walking to Guangxi and stealing a cow. Ten minutes later, I’m fast asleep. Face down, and dreaming about rooster vengeance.

Tea talk

I do have serious conversations, though, ones I feel uncomfortable sharing.

In a nearby village, I have tea with a village doctor, who specialised in sonograms, until they quit. I ask why. “Money,” they say bluntly. But they shift, and I feel there’s something more.

Without asking, they start to tell me about life under One-Child Policy. It hit the area hard. Beijing policy, bumping up against locals wanting big families. As a rural community, children don’t just bring prestige, but help in the fields, and the chance of economic escape. The smartest are sent away to school, to get rich, to ensure comfortable retirements for their parents.

Flaunting the rules was rife. Nearly everyone I meet here has siblings. Many escaped punishment. Others were happy to pay the fines.

Not all got off lightly, though.

They tell me that local women, who’d already had a child, would sometimes be coerced into being sterilised. Many refused, and they’d be locked up. “Some were physically dragged to the clinic, forced to have the procedure,” they tell me.

I think of probing, like how many, what they saw — but then I realise, sat in their amiable company, and seeing their obvious pain, I’d rather not know. I find myself angry not at them, but cadres far away, ramming through the destructive policy. Many there already had big families of their own. Plenty more had mistresses and illegitimate children, stuffed away.

“Of course, it’s different now,” they tell me. “Now doctors are being leaned on not to sterilise.”

Sometimes the urge for family goes too far. Back in the village, a woman passes me, laughing, talking to herself. She’s ‘not quite right’, I’m delicately told. I look closer, it’s obvious she has learning difficulties.

No-one knows the full story, but it’s gathered she was brought to the village by an older man, married, and now has many children. Some of these also have problems. My mouth hangs at the ethics. Privately, locals judge the man too, but in public, they help the woman and children where they can.

Religion is important, here. Buddhism mingles with modern superstition. But predominantly, this is ‘family worship’ area. Each village sports ancestor halls, dedicated to one family, that serve partly as places to hang wooden headstones, and partly as party venues. Empty baijiu glasses cover tables outside. Hakka bonds are strong. Believe me, so is the home brew alcohol they serve at family meets.

After Spring Festival, Tomb Sweeping is the most sacred time. Traditionally, family would return to clean the halls, speak to ancestors, offer food, and pray for blessings. Attendance is mandatory.

Yet, those traditions are lapsing. Younger generations increasingly elect to stay in the cities, or, sacrilege, use the holiday to go travel. Most now show their faces on a video call. The guilty might visit a nearby temple to offer blessings, from afar. While the extra guilty download an app, and sweep digital tombs.

Goodbye

See. There’s an almost unspoken truth: these villages are dying. Beijing regularly refutes it’s anything like other countries, that it has found a different path: Modernisation — with Chinese characteristics. But I’ve seen this all before. I can’t help thinking of visiting Japan’s ghost villages, or cycling through Spain’s abandoned mountains.

In my three days here, I don’t see a single adult younger than late middle age. The only children are infants.

The reason why land is free is because no-one wants it. Youths are in the cities, with the apartments and the jobs. The older generation remain mostly because it’s all they’ve ever known — they were born here, before modern China existed, and hope to die here, too, in earth next to their ancestors.

For all the new mansions and infrastructure, few actually see this place as their future.

Several social media stars have recently built viral channels in China, showcasing their rural life. It’s novelty, a curio. The videos are a fantasy of a place most Chinese never touched, or have long forgotten. A few urban youth were inspired to try it, spurred by Covid lockdowns, though many quickly left. Most watch thinking: ‘rather you, than me’.

When it’s time to leave, everyone is full of restless energy. And I find myself unexpectedly emotional. It suddenly occurs to me, this may be the last time I ever stay in the village. At 90, Nainai is still clambering up slopes, collecting eggs. She’s certainly on top of all the local gossip. But for how much longer?

I stare at the tables in the corner, designed to host an entire extended family, and remember the first time they asked ‘the big foreigner’ to help roll them out. I wonder how many more times they’ll be used.

As the car pulls out — definitely in manual mode — I drink in the village one more time. Slower. Connected. Messy. Human.

Out the back window, I watch it disappear, and my gut misses it already.

When it does, I think China will too.