Two Sessions 2025 — what did we learn?

As China's vapid political circus comes to town, state media hurry to say a lot... about very little.

Question. Is there a busier, yet emptier time than China’s Two Sessions?

The key governmental conference, which brings thousands of lawmakers to Beijing, is a time of great importance … and very little news.

For locals, the event is hard to miss. Smoggy skies miraculously turn blue. VPN’s drop out. Parcels are held back. Traveller’s suitcases searched. A duo of soldiers stand on every subway entrance. And security on bridges now, too, thanks to a couple of banners in 2022. Tiananmen Square comes to resemble the Berlin wall. Armed guards and sniffer dogs patrol the perimeter fences. Dawdlers are hastened on. The Square itself, usually bustling with tourists, turns to a glorified car park. Ambassador’s tinted window Mercs, park alongside reporters’ tastefully patriotic Huawei SU7’s.

Welcome, then, to China’s democratic showcase. Admittance strictly by invitation, only.

During these weeks, state media are stuck in a bind. On one hand, they are the mouth of the Party, tasked with disseminating core messages. On the other, there’s bugger all to report.

Dementia. Eye rolls. President Xi having two cups. It’s not surprising onlookers often get distracted by trivia.

Luckily this week, the Shanghai United Media Group, who own titles like The Paper, Liberation Daily, and Shanghai Daily published a guide. “To make coverage of the Two Sessions more vivid, newspapers can use these five tricks,” it helps. You’ll spot them as headings down the page. The keener of you will spot that two of the headings are basically the same.

“Present Beautifully”

In state media, reporting on Two Sessions is a status symbol. In Xinhua, they have a special canteen just for staff working on it. Table cloths. Flowers. Decorations. And markedly better food and drink.

However, there are drawbacks. Two Sessions journalists are expected to stay at the hotel on campus — even those already living in Beijing. Hours are long. Sunrise, to midnight. Many times I’d stroll through the office to see, frazzled staff, frantically multi-screening, bags under their eyes. What are they actually doing? That’s where I often struggled.

Everyone can agree on one thing: this week is monumental. And each year, also.

This year is “critical” as it is the final year of the 14th five-year plan, say many this year. That goes with what Xinhua called a “pivotal year” in 2024, a “crucial year” of 2023, and a “crucial year” in 2022… etc.

Also a key tenet of hype is that the “eyes of the world are watching”.

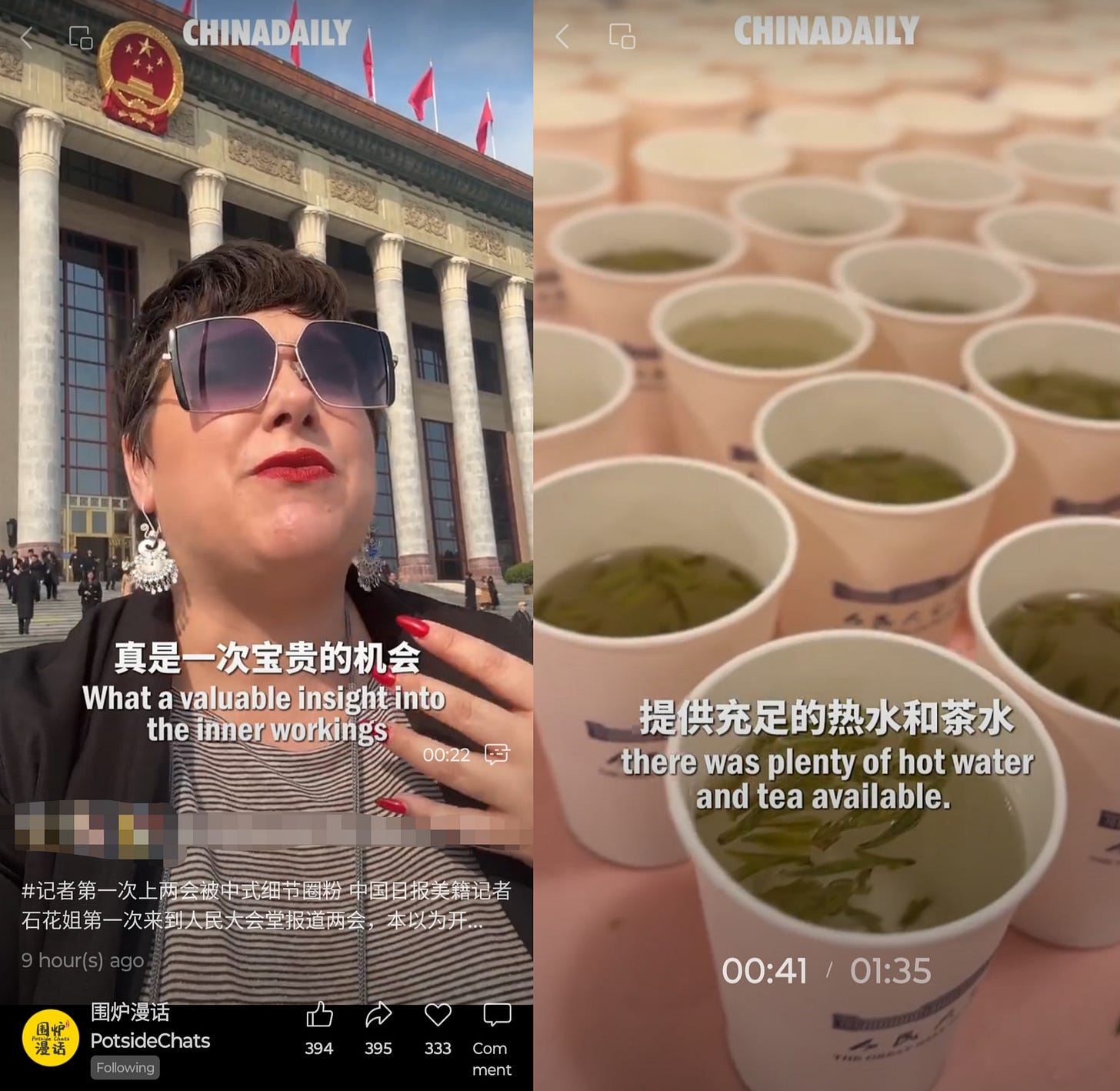

To support this, foreigners are hunted down, to give their carefully edited views. Journalists at big outlets as Bloomberg, CNN, BBC are primed not comment, lest they be used for propaganda. Hence why you only ever see interviews from smaller outlets. Most of the more than 3000 journalists who signed up for this year’s meetings are doing so entirely on Beijing’s coin. Even some of the international ones. These — particularly those from Global South countries — are flown in on state-funded tickets via “media cooperation” schemes. For many, it’s not just their first trip to China, it’s also their first time away from home. Excitable, gullible, bought, they are prime targets for trite praise, for being plastered over state news. Chinese audiences don’t see the context — only the flags, and the praise. “We’re relevant.”

“Visualization of key points”

To ease the workload, various explainers and newspaper pull-outs are pre-prepared weeks in advance. Some with AI.

A few, if they’re feeling spicy, lambast western media labelling their congress a “rubber stamp parliament”. They gloss over the fact that proposals are never voted down, and all are passed near-or-completely unanimously.

Numerous videos and articles also play up China’s “whole-process people’s democracy”, a term President Xi launched at the CPC’s 100th birthday.

“Chinese Democracy starts with the full expression of the people’s will,” says the narrator, in a Xinhua video titled: “Democracy that works”. They skirt over is how these delegates are actually elected, by whom, or the roadblocks put up to candidates.

Other videos proudly point to China’s “multi-party system.” They omit the fact each of these swear fealty to the CPC.

Take “China Association for Promoting Democracy”, a minor Party with 58 seats in the NPC. As the party of “middle and high-level intellectuals working in education, culture, publishing, media and tech” one would suspect this bourgeois hotbed would be a natural opposition to the Communists. Not so, as paragraph one of their constitution makes clear:

“The China Democratic League… accepts the leadership of the Communist Party of China and cooperates closely with the Communist Party of China”

It’s not just lip service, it is enforced. “Article 60. Any member who endangers the leadership of the Communist Party of China… must be held accountable.”

As happened to Yang Guoting, a college dean, who despite being a CDL member, was investigated by the CPC’s own Central Commission for Discipline Inspection and the National Supervisory Commission in 2018, blurring the lines between how independent these parties are. Among various graft charges was that he had "spread remarks that damaged the image of the Communist Party of China and the Chinese Government". He was jailed for eight years.

“Full sense of presence”

Many have criticised China’s media, under President Xi, of moving towards that of North Korea. Less reporting. More jingoism and emotion. This year’s output from China Daily, aimed at domestic audiences, will do little to dissuade that.

A video titled “I cried in the Great Hall of the People” shows reporter Xu-Pan Yiru breaking down, after hearing about the work of a Sichuan delegate. On WeChat, the video received 22,000 likes.

The patriotism extends even to non-nationals. Another video shows American Dylan Walker singing the Chinese National anthem in the Great Hall of the People. “I was deeply moved and couldn’t help but join in,” the China Daily reporter explains.

Dylan, a Communist Party Member of America, also recounts how as a student he suddenly became emotional while watching China’s 70th anniversary military parade: “I stood up in my dorm alone, and sang the national anthem. I was so moved that I shed tears.” That video has 25,000 likes.

Sometimes the coverage can overstretch. One year, an American reporter for Xinhua (who I’ll leave nameless) stood on Tiananmen Square, on the same pavestones where tanks once rattled over protestors, and excitedly proclaimed “China is the biggest democracy in the world”.

Netizens noticed that one. And some media. He didn’t last much longer.

Mostly, though, content has been vapid, focusing on the journalists’ own experiences. Vlogs, vlogs, vlogs, vlogs, and more vlogs.

“There was plenty of hot water and tea,” helpfully briefs first-time attendee, China Daily reporter Stephanie Stone in hers.

What’s also notable is some names who aren’t there. State media employees with large online followings á la Andy Boreham and Jason Smith continue to report on Two Sessions from their spare bedroom and knee-height, respectively. A reminder that prevalence online does not equal importance in real life.

“Use simple numeracy”

Even before the week was over, state media began to push out vainglorious roundups of its own coverage. Partly this is a way to pad content; partly it’s a paper trail for Party superiors. “See. We did our duty. Keep the cheques coming.”

In one, the SUMG chief said their group had “effectively implemented the work arrangements of the Municipal Party Committee Propaganda Department”. “Since February 28, SUMG have published more than 130 newspaper special pages, more than 3,100 graphic reports, posters, short videos and other integrated media reports, and 70 live broadcasts,” the report boasts.

Their actions were rewarded with a visit from the local Propaganda Bureau, who praised them for “conscientiously implementing the requirements of the Publicity Department”.

“Comment on key issues and speak the truth”

China’s Two Sessions is an odd form of “democracy”, as some persist to call it. One I got to witness first hand, though not that I had much say in that — my boss signed me up without telling me, wouldn’t let me back out. Security checks took months for my pass, one that let me wander the halls even when media (international and domestic) had been kicked out. I also remember being rushed to a small room for a personal pep talk from Li Zhanshu, the then Chairman of the standing committee of the NPC, and China's number three. His words went over my head: I was far too distracted by his bodyguards glaring at me.

While in hindsight grateful for the experience, and genuinely profoundly moved by a lot of the delegates’ civic pride and actions back in their hometowns, it also firmed up my views of the system.

My overriding memory of the Great Hall is the echo of one man reading a report, and 3000 delegates listening along. It’s hard to define democracy — but in that moment, the sound of 3000 people turning their pages in unison, I knew that ain’t it.

I never understood China’s haste to mislabel itself. Paragraph one, line one of the constitution runs: “The PRC is a socialist state governed by a people’s democratic dictatorship”. General consensus in China understands this — and mostly is fine with it. Overseas, practically no-one misunderstands. Only a small band of external propagandists continue to insist down is up.

My own small rebellion came during Xi’s vote to abolish term limits. The result guaranteed, I’d already filmed my piece to camera ahead of the event. As hundreds of journalists clamoured to see the public knifing of the constitution, I didn’t. I knew it was history in the making: I just couldn’t bear to witness it. So I sat outside, alone, in the cavernous hallway, sipping tea. When applause broke out in the auditorium, I stood, and quietly left.

That’s the problem with China’s ‘people's democracy’. It can operate without the people.