"No speed. No ability. Can't tell stories". Why China is turning to 'media studios' to revive its propaganda

These 'Light Cavalry' are designed to be small, nimble, and camouflaged — just don't ask them who they work for.

Read Chinese news in recent years, especially on social media, and no doubt you will have seen a bright-eyed journalist tell you about the “real China”. Probably a vlog. Or an animation. Or a Substack.

The content looks like propaganda. It feels like propaganda. The hosts, some with millions of followers, have incredible levels of access to high-profile Chinese events, or areas. Only: there’s no markings. Credits and logos (if any are given) just cryptically list the “xxxxx studio”, typically the name of the person on camera.

Western journalists and researchers were very quick to pick up on these profiles, and note their state links, identifying them as covert propaganda campaigns. But, in a way, they also missed the underlying story.

You see, China's state media is currently undergoing a mini-revolution. The Chinese Communist Party, the largest, most centralised government in human history, is realising that perhaps it is the problem when it comes to 21st century storytelling. Inflexible dictatorship may be great for orchestrating grand construction projects, or military parades — it’s less effective at creating a good TikTok.

Perhaps, it’s wondering, do creatives work better with a little freedom?

This, then, is the story a new(ish) model for the CPC: the “media studio”. What are they, why they were created, how they work~

“Must love the Party’s journalism”

Chinese State media is an inefficient mess, staffed by people who don’t know how to tell stories.

Those aren’t my words — but from the industry itself. Last year, Sun Shangwu, Deputy Editor of China Daily, wrote in a prominent magazine that Chinese journalists:

…lack speed , with authoritative sources often unable to speak immediately on hot topics and emergencies, resulting in missed opportunities for response; lack warmth, with some parties lacking strong storytelling skills in international communication practices, and their communication and empathy skills need improvement; and lack force, with both the ability to strengthen agenda setting and persist in long-term efforts on major issues, as well as the need to achieve immediate results in response to Western slander and attacks.

Cheers boss. But he isn’t wrong.

As sweet and welcoming as most my colleagues were, it’s not a secret to announce that more than a few weren’t very good at their core jobs. It wasn’t intelligence, they were incredibly bright, rational. Nor was it the language barrier — I lost count of the times I had my own grammar corrected. It was more the fundamentals of storytelling: spotting the lede; passion for the subject; audience empathy; deep, wide knowledge.

A more critical flaw among most external propaganda workers I met: they simply didn’t understand how foreign audiences think, even those who had lived abroad. They couldn’t predict blowbacks. They lacked self-awareness.

As an outsider, it wasn’t hard to finger why.

China’s school system is legendary for its competitiveness — Tsinghua University has an acceptance rate of around 0.1 percent. Top state media, like: Xinhua, CCTV, People’s Daily are just as brutal to get into. They hire only from the top universities, yet each graduate position can receive a thousand candidates. Do the maths: that’s 0.1 percent, of the top 0.1 percent. Or to phrase it another way: in China: these are one-in-a-million jobs.

Outlets believe they are hiring the very best. But is that true..?

Joining state media, candidates are mostly whittled down via multiple interviews, and written exams designed to test a candidate’s “political stability” or to ability “fit in”.

Take this recent job advert for a Video Editor at China Daily. See if you can spot where HR priorities lie, and how the organization may not be hiring the most creative.

Basic Requirements for Application

(1) Be a Chinese National.

(2) Have a firm political stance, support the leadership of the Communist Party of China and the socialist system, firmly establish the "four consciousnesses", strengthen the "four self-confidences", and achieve the "two safeguards".

(3) Support and abide by the Constitution and laws and regulations of the People's Republic of China, practice the core socialist values, be honest and trustworthy, have good conduct, and abide by rules and disciplines.

(4) They must love the Party’s journalism work, abide by the professional ethics of journalists, love international communication, and have good professional ethics and team spirit.

…on and on, until finally, at point number 6:

(6) Have the professional skills to meet the job requirements.

Squish all those recruits through this tight, highly-ideological pipeline and it’s no wonder the few who pop out tend to write articles that read like lumpen, statist college essays. It’s what they’ve been taught — and rewarded — to do, their whole lives.

It’s not that witty, self-aware, digitally-minded creatives don’t exist in China — go browse Douyin or Xiaohongshu for five minutes. It’s just that these individuals tend to be filtered out at every step of the hiring process.

These. These recruits are the ones now expected to “tell China’s stories well”. At a time when old media is crumbling. When deadlines are instantaneous. When stories are expected to be multimedia. And to do all this, while under fastidious, ever-changing censorship rules.

And that’s just domestic. For those targeting the international eyeballs, the task is even harder. They also have to operate in a foreign language.

The stakes are high. And the consequences can be very real.

Not many can adjust to this high-wire act. Many flop. The majority deliberately become risk-averse, repeating the hegemonic lines, choosing to work on, head down, serviceably dull, eating from their iron rice bowl (铁饭碗) for life. Very few thrive.

“The key to media competition is talent competition” Xi Thought on Culture

However, the Party isn’t blind to this. It is increasingly desperate to control the narrative within China, and abroad, too.

As Xi’s Thought on Culture puts it: “We must push forward onto the main battlefield…accelerate the construction of a new mainstream public opinion landscape that.. integrates internal and external propaganda.”

Frustrated at its own lack of cut-through, the Party has recognised it needs to enable journalists to succeed in spite of the stifling conditions it forces them to work under.

How to unbridle individuals with a natural knack for storytelling, a thirst for competition, and most of all: the ego to be seen?

Simple. Give them their stirrups.

“The studio format breaks down the barriers between departments, industries, and types of work. It is more flexible and efficient than traditional media content production methods. It is an active exploration to optimize organizational structure, innovate content production, and expand product impact”

The Hanfeng Media Institute

“Light Calvary”

Studios, in my experience, were largely an accident. At first, they were IPs set up underneath state media programming. Xinhua presents: The Deer Show. Etc.

But quickly, the industry started to notice a few endemic advantages to this approach.

Rather than file content to conveyor belt, these small teams worked more like entrepreneurs, project-to-project. Workers are invested in their content. Its success is their success. This encourages risk taking, creativity.

For those who front these IPs, leant their image, the rewards are greater. In an industry where salaries are low, and office politics strictly hierarchal, these products offered a chance for individuals to stand out, and earn ancillary rewards like cash bonuses, trips, and fame.

The industry also discovered another boon: camouflage.

Contrary to public opinion, state media doesn’t just have a reputational problem with foreign audiences: it has a connection problem with Chinese viewers too. It’s respected domestically, for sure. And some videos — especially around the Party leadership — are gobbled up. But it’s not…. cool. It’s devoured in the way one does their vegetables.

Another problem state media has, is authenticity. By being so overtly propagandistic, it becomes hard to believe. Viewers feel as if they’re never getting the whole story.

From data I saw, and my own experimentation, Chinese audiences are much more willing to engage with content the less obvious it is a piece of state media. By pushing ‘independent’ IPs, especially those based around a “star” or influencer, bosses found audiences more liable to make personal connections. More likely to internalise the video’s opinions as their own.

It’s a clever propaganda trick. All the heft of state media: none of the baggage.

Landscape today

Today, there are perhaps a thousand state-run media studios in China. Anhui Radio and Television Station alone has 65. Shanghai United Media Group has 35.

The biggest are huge. The Green Hornet studio, launched by China Youth Daily in 2017 has been viewed 100 billion times.

The vast majority are directed wholly at the Chinese domestic market. While every single one, engages in what the Party euphemistically calls “public opinion guidance”, many are innocuous, and often specialised to a specific theme, like a duo rapping, elderly health, or this one of Claymation animals.

The model has also been brought down to student level. In May, the Xuanzhou District Youth League Committee established a youth media studio, with the stated aims of “Party building” and “deepening the Party's leadership over talent”.

What’s interesting — and more problematic — are the studios directed specifically at overseas viewers. Since Zhou Enlai in the 1950’s, China has been committed to a policy of “non-interference” in other country’s domestic affairs; it’s Chinese law.

Yet, some of these studios are doing just that.

‘Light Cavalry’

“The purpose of light cavalry is primarily raiding, reconnaissance, screening, skirmishing, patrolling, and tactical communications.” Wikipedia definition.

Internally, these studios are referred to as “Light Cavalry”. The military term is an ode to the CPC’s revolutionary roots, common in Party material, but it also captures the essence of these studios so damn well.

These are the exact aims of the more political studios. Designed to move quickly, probe hostile stories, look for weak spots. Once they find solid narrative ground, the state can rush in behind with its full complement of troops, to support.

Explicitly political studios, aimed primarily at international viewers, by top-tier state media were until a few years ago, rare and crude. Notable examples include Xinhua in 2017, People’s Daily in 2017, or China Daily in 2019.

In 2019 however, the China-world got a lot more political. Hong Kong protests. Xinjiang. Covid. A wave of nationalism hit state media. “Wolf Warriorism”, as it was dubbed.

The world’s social media platforms responded by labelling, and then throttling Chinese accounts. Views fell by around 90 percent overnight.

Immediately, the benefits of camouflaged IPs became obvious.

Within months, state media journalists began launching or rebranding their own personal social media profiles. They were backed by huge promotional campaigns — some paid adverts were seen by over a million foreign users.

Many were caught, and too, were stamped. Often they were outdone by their own greed — ad campaigns too large, content too political, or submitted details too suspicious. New accounts were tried. And so began a game of cat and mouse.

If anything, these tactics, and their ‘Wolf Warrior’ content had a disastrous effect on China’s reputation overseas (told previously).

But Party leadership, and media academics are currently sold on the model.

At the Third Plenary Session of the 20th CPC Central Committee in 2024, Xi proposed China: "build a working mechanism and evaluation system that adapts to the production and dissemination of all media, and promote the systematic reform of mainstream media." That only fuelled change.

From around 2021, the studio experiment became a nationwide push. At conferences, chief editors announced “Media Integration Studio Empowerment Plans” and a raft of new studios — often in a game of one-upmanship.

At the China New Media Conference in Changsha, last October, 110 “outstanding media studio case studies” were announced. One we will discuss in the future.

How it works

“Led by the manager, a "small but elite" team is formed, and each team member has multiple duties, forming a low-cost "innovation-trial and error" mechanism to implement organizational change under an Internet-first thinking.”

Shanghai United Media Group

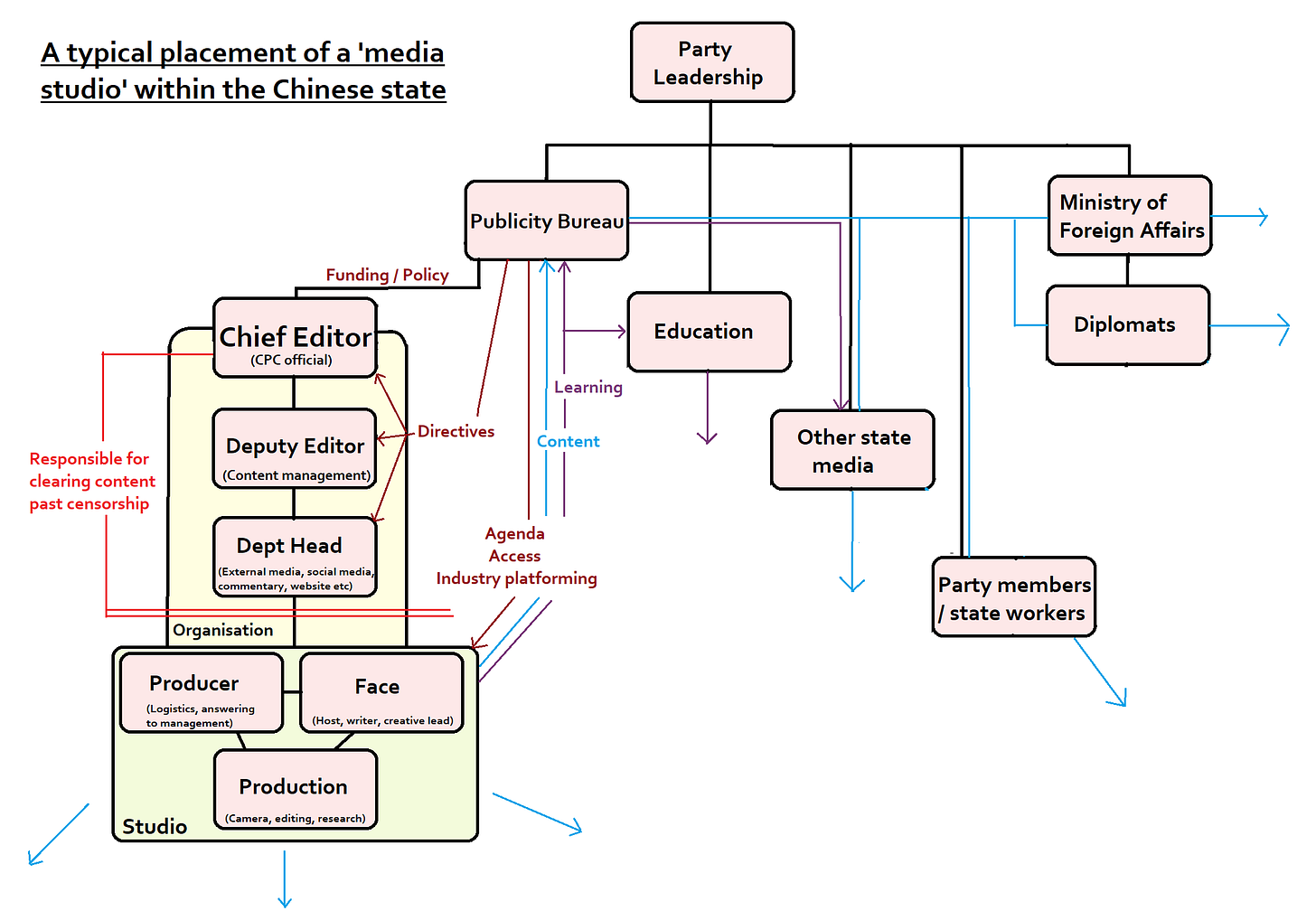

A typical set up might look like:

Face. Typically, the creative thrust. The host, or personality who loans their image to the studio. Quite often a video journalist who self-shoots, writes, livestreams or interviews.

Producer/Convener. Handles management, logistics, censorship. These members liaise with the Party/senior management, and are instructed on upcoming special content themes to be covered.

Production. Perhaps one or two people to help assist production — camera, research, writing, graphics, subtitles, video editing. Often interns placed here.

Sizes vary. Some studios can swell to a dozen or so for big shoots. Sometimes a studio is just one person running a Substack newsletter, alongside their day job.

“A video journalist with professional skills, a strong focus on innovation, and a passion for creativity will be selected as the head of the studio” Jiaozuo Daily

If they become really successful, the studio may be funded to go full-time. Here, the unit is explicated from their original teams, and become their own quasi-department, to work full-time on content.

Before, where they might report to the department head, now they may report directly to the Deputy Editor or above.

“The model is not a "beehive-style fixed layout", but a "task-oriented" flexible collaborative layout. Work is started on demand.” People’s Daily

While the idea is to keep these studios small and light. The studios are also expected to promote themselves and be promoted across the industry, as flagbearers for the media organisation. Often, they will give lectures at industry conferences, lectures in Chinese universities, and submit academic articles.

In return, the state will back them, with:

Accreditation. For key events, in addition to the outlet’s regular journalists.

Amplification. Successful videos are run back up and out via tentacles of the state.

Advertising. Via spend on foreign platforms (Facebook ads, X promoted posts etc), bot farms, and PR firm contracts.

But why explain this relationship, when we can see an overly complicated, crassly drawn chart:

The first thing you should note, is that the studios or its faces are often not responsible for censorship. Instead, they mostly exist in a hybrid world of largely self-censorship.

Content creators are not daft. They know the general political lines — as everyone inherently does in China. They are also aware of the implications for their careers.

To make sure though, Party doctrine and Xi Thought are reinforced in specific political training that all registered journalists have to undertake to keep their official accreditation, either via the Xuexi Qiangguo app; in regular company cell Party study sessions; or in annual away day refresher courses.

“Each studio's project is independently approved. A convener forms a team and develops a plan for the project, including creative themes, presentation methods, target audiences, publishing platforms, planned number of projects, project sustainability, and expected social and economic benefits. A review committee then determines whether the project should be approved.” Beijing Daily

Actual responsibility, and final say over clearing content, typically lies with senior management — active Party members, cleared to do so, after spotless records, and long, intensive, and regular training.

This system is clever in that it gives political cover to these supposed “autonomous” frontline content creators — especially useful for foreigners, or those working on outward-facing content. “These opinions are my own”, “I write what I want”, “I’m just a journalist”. Technically, these statements can all be true. They just have hefty, hefty asterisks against them.

Sometimes the censorship process is explicit, and negotiated pre-publication. Large content mostly has to be vetted and signed off in advance, particularly: videos, articles, political commentary. Commonly, these have several eyes on them, and nearly always if they deal with sensitive subjects (CPC leadership, Xinjiang, Taiwan, Hong Kong, the military, or foreign state leaders etc). With smaller content such as social media posts, the process is retrospective. Posts are simply monitored, and later ordered to be deleted if problematic.

Content is two-way. The vast majority is self-initiated. However, sometimes, this is also expected to fit around an agenda handed down, often to coincide with ‘hot topics’ and wider national narrative pushes. These are blocked out weeks, sometimes months in advance.

“Studios are deeply embedded in the company's key topic planning, providing reporting resources and supporting their participation in coverage of major topics and events, such as the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, the Two Sessions of the National People's Congress, manned space launches, and public opinion work on the United States and the West.” Xinhua.

Certain lines or directives may get handed down from the Publicity Bureau, Cybersecurity Bureau or others: “It’s Xizang, never Tibet”, “Emphasize that the Beijing military parade ‘demonstrates peace’”, “Don’t attack Trump directly” etc. Some content creators — particularly foreign ones — are deliberately omitted from this process. Instead, they are instructed via feedback from management, or largely left to figure out boundaries on their own, often by trial-and-error of what gets rejected.

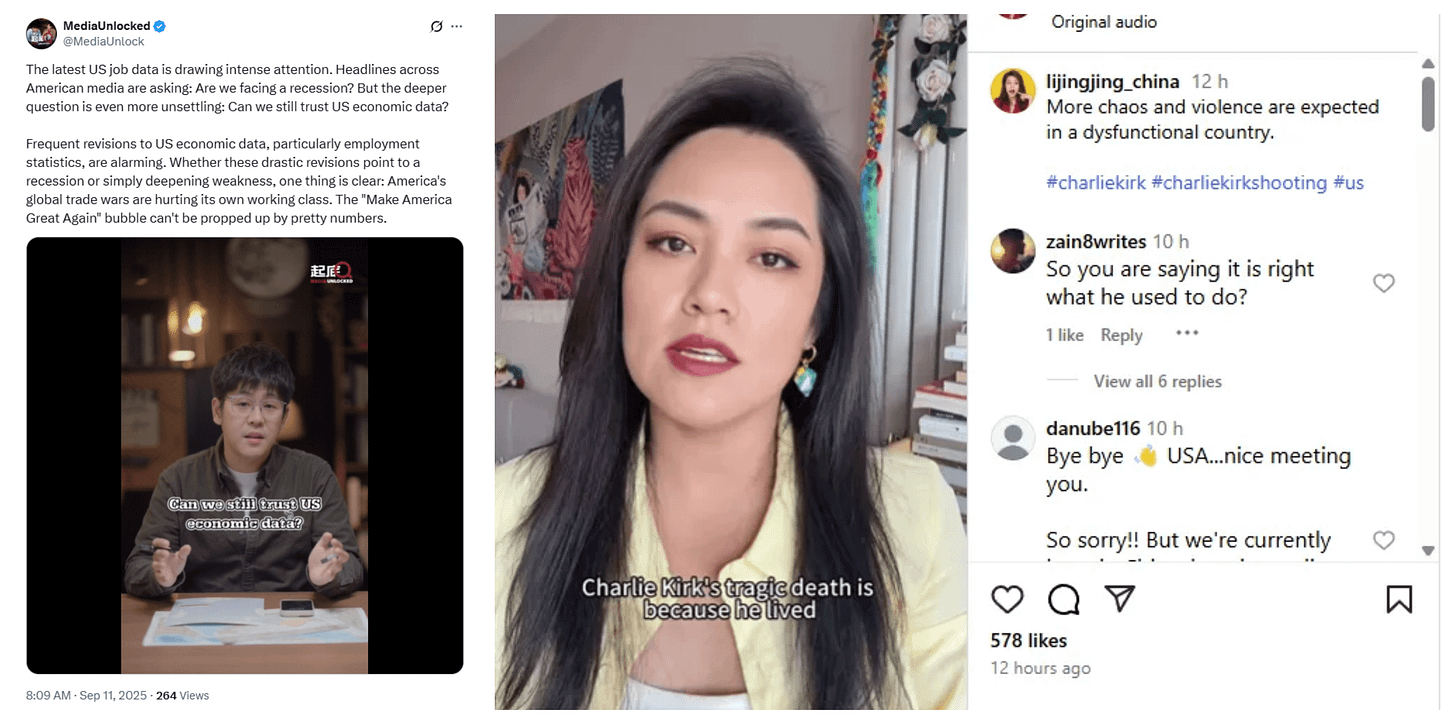

To help, some well-known foreign-facing media studios run WeChat groups; some include “independent” ‘pro-China’ content creators. Here, they share news, float ideas, and formulate possible rebuttals to stories damaging to China’s government. These lines are then hammered across all their individual channels, in a wall of coordinated action, sharing, and cross-support, in an attempt to drown out or delegitimise the story.

According to sources within these groups, members have also used these chats to plan coordinated attacks on foreign reporters. After, they often privately share and celebrate social media harassment their campaigns sparked.

With such interoperability, it’s never a surprise to see faces of these studios in the same place, on the same day, covering the same issues.

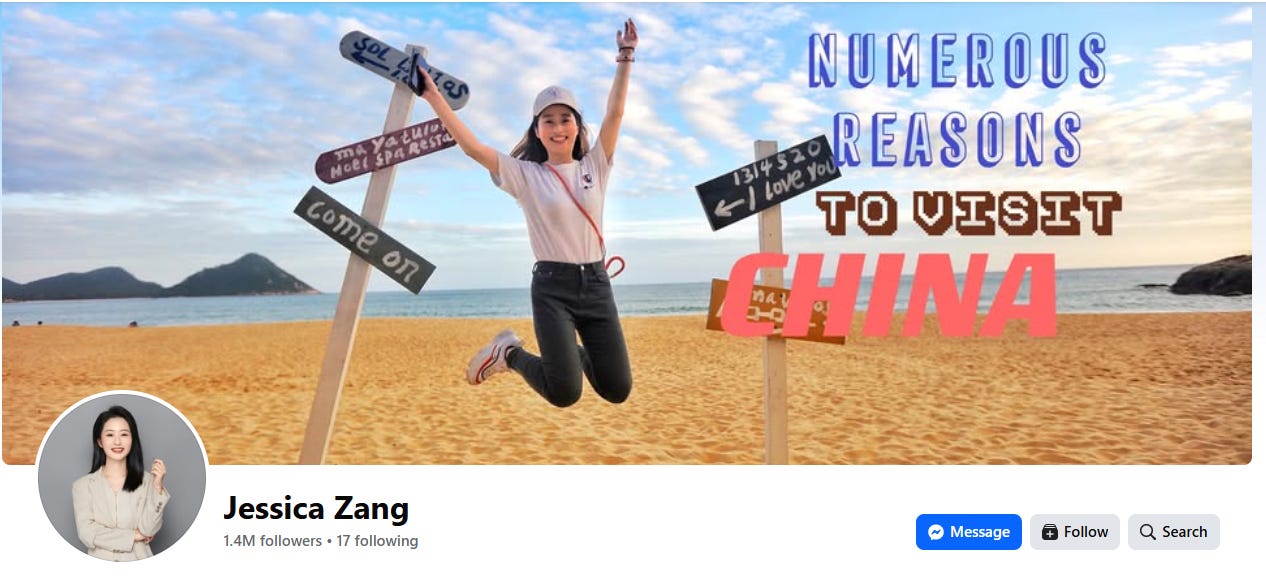

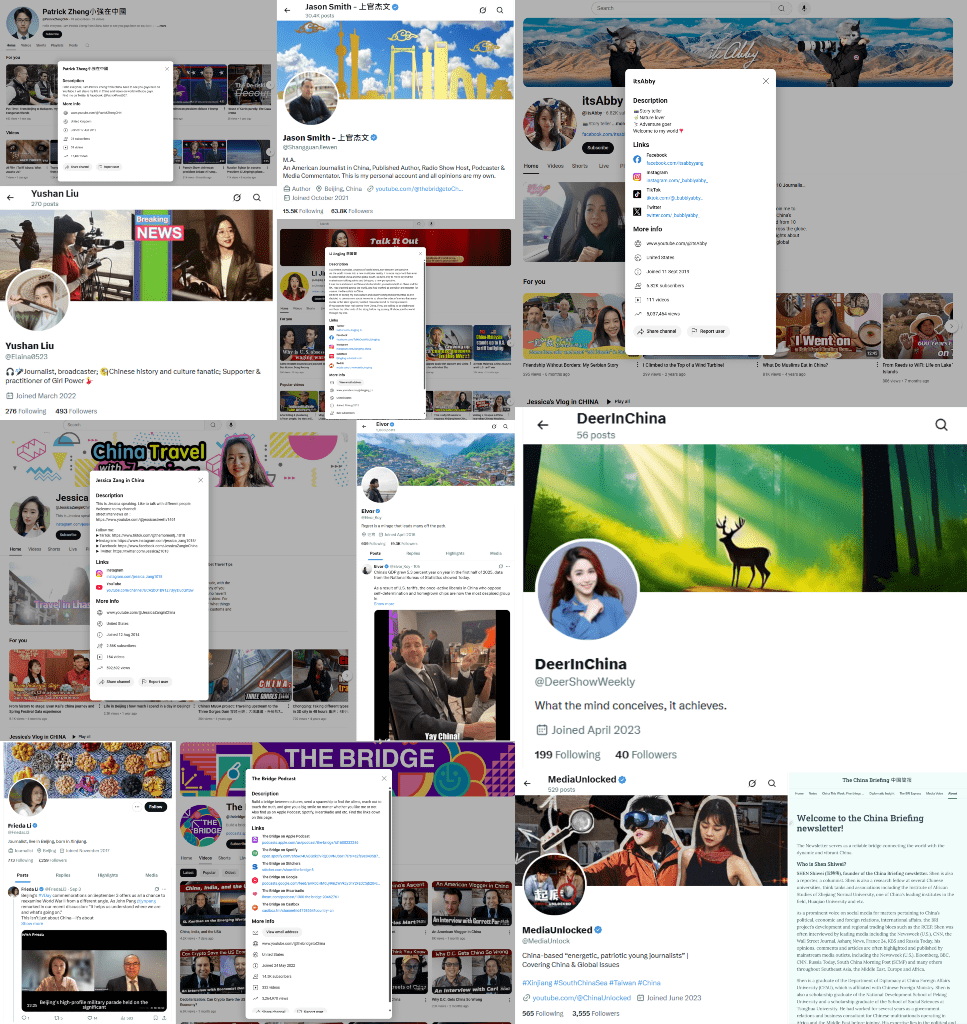

Camouflage

Every single one of these accounts is Chinese state propaganda. There’s plenty more, but what sets these profiles apart is not one mentions their state background in their bios. Instead they are “journalists”, “editors” and “social media addicts”. Considering they all are, or work for, a studio tasked explicitly with targeting overseas viewers, that seems a rather deliberate omission.

To repeat — most Chinese state media and journalists are completely harmless. Workers storytelling, making the best in their favoured career, in a country that the geographic-roll of life gave them, under increasingly trying political circumstances.

But a minority are pushing the realms of ethics, under the wing of an expansive state. Who cheat. Take shortcuts. Drive divisive narratives. Are duplicitous. Some who do it mainly for ego, career advancement, at the reputational cost to the wider industry.

To that, I say: fine.

If it’s attention you want, perhaps we take a closer look at you. ✨

![54557_1716371299_transv (2).gif [speed output image] 54557_1716371299_transv (2).gif [speed output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!yYVp!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F791aef10-e1f8-4f06-9a48-bcd2015fbccd_480x360.gif)

Well said!

“These lines are then hammered across all their individual channels, in a wall of coordinated action, sharing, and cross-support, in an attempt to drown out or delegitimise the story.”

Has got me thinking a lot lately about this piece by Gary King and Jenn Pan on how propaganda these days is for distraction not engaged discussion:

https://gking.harvard.edu/50c

They are also on Reddit :D