Where did all the laowai go?

China has loudly been telling the world its tourist industry is booming. Videos show legions of happy tourists. Yet numbers tell a different story...

Read the Chinese press, and you’d swear the country is currently the world’s hottest tourist destination.

According to official figures, in 2024, a total of 64.88 million foreign citizens entered or left China — up a staggering 83 percent in a year.

A “surge of foreign tourists” say China Daily. “Foreign tourists flock to China” went People’s Daily. State media have also fallen over themselves to explain what is propelling this flurry.

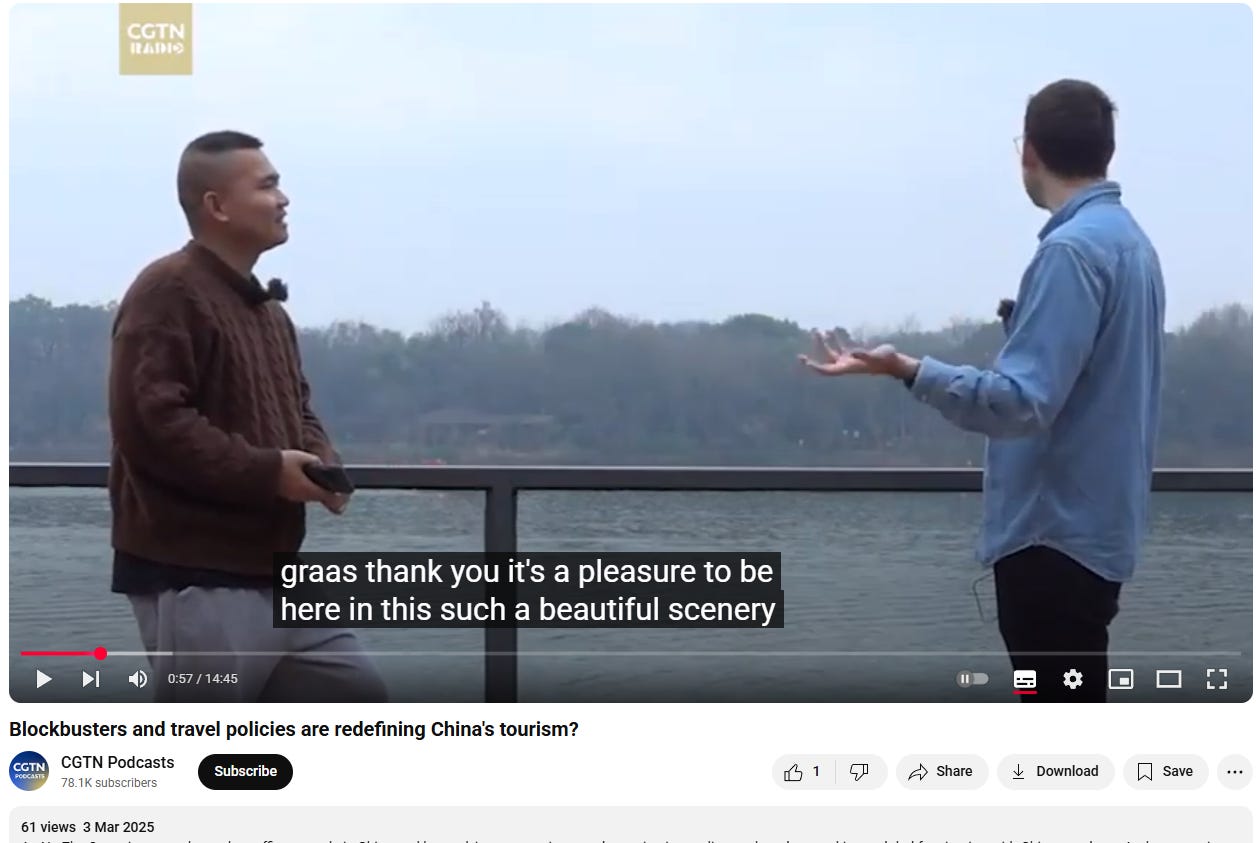

Reporting from the “beautiful scenery of Guilin” on a visibly polluted day, CGTN suggested it was due to the “global rise in Chinese movies”, particularly Ne Zha 2 — a brave claim, considering less than 2% of the film’s receipts came from outside China.

“What's behind China's international tourism boom,” CGTN host Liu Xin posted on X this week, promoting a segment on her show.

“The Government’s policies,” her guppy panellists answered.

And it’s true. Beijing has made a huge concerted effort to make to attract foreign tourists in recent years. A quarter of the world can now visit China visa-free. And 55 countries can visit (parts of it) for 10 days.

There’s also been a raft of other measures, like accepting overseas payment methods, VAT rebates, or allowing tourists to visit Facebook, X, and other banned apps, while roaming.

But there’s also one more key facet driving this so-called tourist boom: bullshit.

Only when you drop down to more venerable outlets like Caixin, does the true picture start to emerge. “China Bets on Visa Waivers to Get Tourism Back to Pre-Pandemic Levels” runs a headline this week.

And here’s the crux. There is no tourist rush. This is no golden age.

Today, China today has fewer foreigners, not more.

…what boom?

Compare 2024’s figure of 67 million foreigners entering and exiting China to that of the 2019 peak.. 97.7 million.

It cannot be overstated how devastating the Covid pandemic was to China’s tourism industry, and expat community. For six months, the country was shut off (—though not for one prominent person. See end*).

In comparison to those days, and China’s delayed reopening, of course current figures look a sparkling success, hence state media often using “year-on-year” statistics.

But despite the headlines, tourism industries say they are struggling.

Hilton, Marriott and other hotel chains have all announced their revenues per room fell last year in China — that’s despite revenues going up in other parts of Asia. All say the same thing: inbound tourism isn’t hitting the numbers promised, and locals are tightening their spending.

Flights too.

“Chinese and foreign airlines operated an average of 6,395 international passenger flights per week, representing 83.9 percent of the level recorded in 2019,” reports China Daily. Somehow that decrease ended up with the headline “Q1 int’l air travel soars to new heights”. Nice spin, boys.

European airlines in particular have been hit by the Ukraine war, and the resulting flight ban over Russia, adding hours to flight times to Asia. British Airways, Lufthansa, Virgin, LOT and more have all cancelled China routes, saying passenger numbers are too low to support these higher costs.

However that doesn't explain pullback from other regions. In July, Qantas cancelled its last China flight (Sydney-Shanghai), admitting planes were often “half-full”. Meanwhile US airlines have begged authorities to excuse them from flying their full quotas. Last winter, United, Delta and American operated just a third of their possible flights to China citing “low demand”.

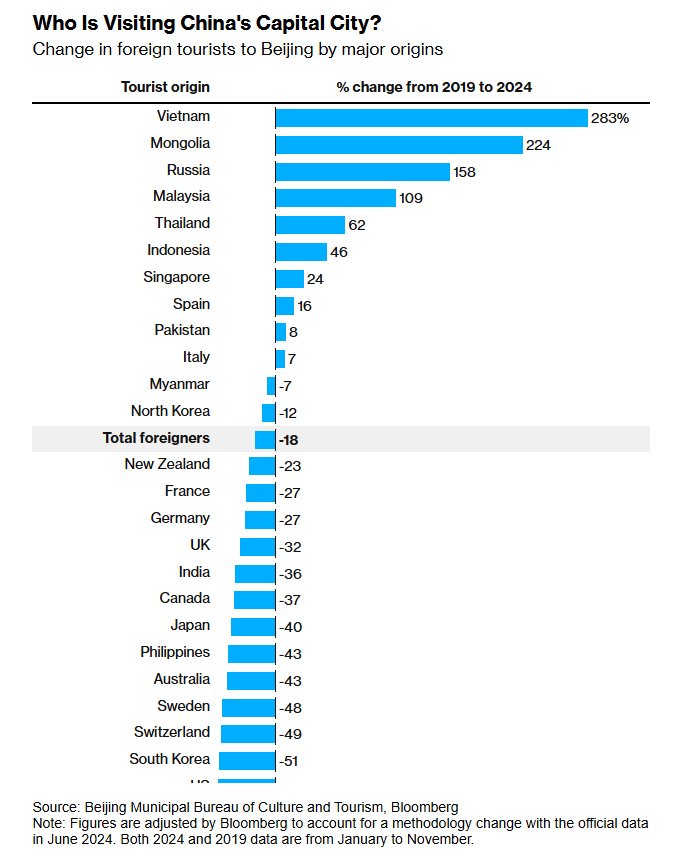

It’s not just raw numbers, but who’s coming.

Consult Chinese propaganda, and you will see a wall of young, often white, tourists. However, the actual makeup is very different. Tourists from US/Europe are falling — not rising.

Disguised in the top-line figures, too, are the tens of thousands who live near China’s borders and regularly cross for work, business and shopping — particularly from Vietnam, Russia and Mongolia. Each one of these individual visits is recorded as “a foreign entry” by border control, helping to inflate annual figures.

The foreign number also masks the huge number of Chinese overseas diaspora, living overseas, holding foreign passports — as anyone who’s waited at immigration can attest.

At London Heathrow airport, a few months back, when I passed the check-in line for the China Southern Shanghai flight there were maybe a hundred people: not one wasn't of Asian heritage.

How many foreigners call China ‘home’?

The fact is there are significantly less foreigners living in China today, than prior to Covid.

China handed out 730,000 residency permits last year. That’s down on the 900,000 in 2019.

But buried in the annual National Immigration Administration press release was a more startling statistic, one I’d never seen reported before, and the more I thought about it, the odder it became.

In 2024, China granted 74,000 residence permit extensions.

That means either ~90 percent of foreigners stay just for the length of their visa, before leaving for good. Or, individuals are flying back to their home countries, completing the paperwork there, before flying back to live in China on brand new visas — which seems… faffy.

If it’s the former, China’s settled expat population could be much smaller than many imagine.

The figure is bolstered ever so slightly by the 12,000 people in total who’ve obtained permanent residency since China’s ‘green card’ scheme launched 20 years ago.

Yet, even together, that means the total of China’s settled foreign community comes to less than the capacity of the Bird’s Nest stadium… For a country bigger and more populous than Europe.

In the past, China also had a large ‘unofficial’ expat community, nominally on tourist, or spousal visas, but working locally on the sly — this too has dwindled.

In 2019, officials estimated the country had a million foreign teachers, of which, only ten percent had ‘sufficient qualifications’. Primarily, they worked in private English education — until that industry was obliterated by Beijing in 2021.

Today, nearly all those expats are gone. State education, too, is a shrinking sector thanks to China’s demographics, and some lawmakers calling for less emphasis on English.

It’s a similar story across other industries too. A few months back, I was surprised to get a call from a CCTV recruiter — especially because the last time I spoke to them in 2021, it was to be told I was blacklisted [and this was pre-posting online!].

“You’re reaching quite far back?” I asked.

They sighed. “No one is applying, and I can’t find candidates.”

They went on to tell me their job is currently impossible. Foreign staff numbers halved during Covid “and never recovered”. Hence digging through dusty CVs. At one point, there were fifty editor vacancies, they told me, before bosses realised they were never going to be filled, and started liquidating positions for good.

They asked if I knew of anyone willing to apply.

Then, sheepishly: “Also. Do you know of any jobs in the UK… for me?”

Underlying problems

In many ways, the Chinese government is fighting problems it itself has created, or has fuelled.

Take the surveillance state.

Under Chinese law, all hotels must register the details of foreign guests with a local police station within 24 hours. Unwilling to do this extra legwork, many hotels — particularly the cheaper or more rural ones — have long just turned foreigners away. The government has repeatedly ordered hotels to comply, but reports say many still refuse.

Like many countries, China also has a deep vein of xenophobia, often fanned by the Party. Told now “to open up”, it’s only natural there is confusion, and resistance.

In 2020, when the Government announced it was going to relax rules, making it easier for foreigners to get permanent residency, there was an instant backlash online, with over 3 million, mainly critical, comments on Weibo.

“In a hundred years’ time, I don’t want China to have become like the U.S., with all kinds of people mixed together,” wrote one user, to 23,000 likes.

This struggle can also be seen on the street.

At the same time as trying to attract tourists, cities have been busy de-anglicizing their place names, from English translations to pinyin. What was once marked “Beijing West Station” on the subway map is now called “Beijing Xi Zhan”. “Capital Airport Terminal 3” is now “3 Hao Hangzhanlou”.

Some people face tougher welcomes than others.

A Human Rights Watch study found black people to be routinely mocked on China social media — an issue dissected by a BBC investigation in 2022. The CPC claims China is a tolerant country, yet Blackface in the national gala, brownface in state media videos, or by the Ministry of Public Security and adverts showing ‘black men washed clean’ have done little to dissuade.

Even influencers known for their China-positive social media have caught flak, such as King Kwesi, who in 2023 asked followers to be respectful, following a spate of racist abuse on WeChat.

Discrimination can also be seen in the country’s visa policy — as one state media worker inadvertently highlighted recently.

In May, Shen Shiwei — whose X bio plays up his "years in Africa", but forgets to mention he works for CGTN — posted how China is now "VISA-FREE" for 47 countries.

Soon, however, African followers spotted how the extensive list doesn’t feature a single nation from their continent.

Within a day, the post had gone viral, racking up a million views, a thousand incredulous shares, and a thousand mostly negative replies.

“It’s always funny how the Chinese never include Africans on these lists,” surmised one popular comment. “Africa always likes to say China is the all-weather friend but it doesn’t seem like this friendship translates to welcoming their “friends” from this continent.”

In short: there’s work to be done.

A turned corner?

The most recent figures for Q1, 2025 show China continues to attract more foreign tourists each quarter — but it’s still lags about a third down on 2019.

It’s a shame, as China certainly has the goods. The vast, continent-sized country features nearly every biome possible. From the Gobi desert, to the jungles of Yunnan, to Hainan tropical beaches, to frozen winters of Heilongjiang, to the iconic Yellow Mountains. Featuring Pandas. Tigers. And bears, [oh my]. Some glistening cities. Svelte infrastructure. And oodles of polite, friendly, curious people.

It is, and should be, a tourist goldmine. And yet…

As with everything in China, the biggest deterrents are mainly political. And as long as they remain, the PRC will always have an asterisk, preventing some from coming.

Take my friend, a doctor now living in Australia. Liberal. Well read. Recently, she wanted to visit England with her family. The options were fly back via the Middle East — obviously troublesome given the recent news; or a 12-hour stop in Singapore. Tickets for her dates were ~$1400.

I suggested going via Shanghai instead. Not only were the flights cheaper (~$800), and faster, but there was an option to book a long layover, with the airline even throwing in a free hotel for the night. And with their EU/Australian passports, they could enter visa-free. “Save the cash. Pop into town. See the sights,” I suggested.

“China? Hmm. We’ll pay extra, and take the wait, thanks.”