What is President Xi's legacy..?

So far, his tenure has been one of borrowed wins, sputtering projects, and debt. A lot of debt.

It’s easy to be awed by Xi Jinping’s current status.

China’s President is routinely labelled the country’s most powerful leader since Mao. He heads so many commissions, he’s nicknamed the “President of Everything”. He commands two million active soldiers — the world’s largest standing army. He’s leader of the world’s second biggest political party, which has just topped 100 million members. A Party, which under the principles of “People’s dictatorship”, has coopted every facet of the state, from justice, to media who now have to swear felty to keep their jobs. Political rivals waste in jails. His airbrushed portraits dot the countryside. And in schools, children study his speeches.

Xi, as the constitution reminds us, is China’s “core”.

And yet.

Every so often, nonsense rumours scuttle around Chinasphere, that Xi is in trouble. That the 72 year-old leader has developed health issues, or is fending off an attempted coup. When they do, after ignoring them, I start noodling on the same question. How exactly will Xi be remembered?

All taken, if his Premiership stopped tomorrow, how will he be rated?

Because, a feeling I can’t seem to shake, is that future historians — even those of the Party, currently pumping out endless obsequious books, fêting his genius wisdom — will struggle to celebrate him.

Doubt it? Then answer this: what exactly is Xi’s legacy?

It’s actually surprisingly hard to accurately mark Xi’s scorecard.

Hindsight makes it relatively easy to pinpoint successes of previous Chinese presidents, their defining characteristics. Mao needs no explanation. Deng Xiaopeng’s earth-shattering economic reforms, that eschewed communism and paved the way for China to transition to a market-based economy. Jiang Zemin’s great state liberalisations, the “Go Out” policy, and China’s joining of the World Trade Organisation. Hu Jintao’s globalization efforts, explosive domestic growth, technology transfers, and quiet but effective international diplomacy.

But what of Xi?

The quest is hardened by the fact that many of the poster childs for Xi’s New Era, often plastered across state propaganda aren’t exactly his own projects.

China’s High Speed Rail network? That was greenlit by Jiang, and mostly developed under Hu. China’s space project? A never-ending development, stretching back to the 1950’s. The C919 passenger jet? A hodgepodge of foreign-bought tech, on a programme launched under Hu in 2008.

Even national cause célèbre’s are dubious.

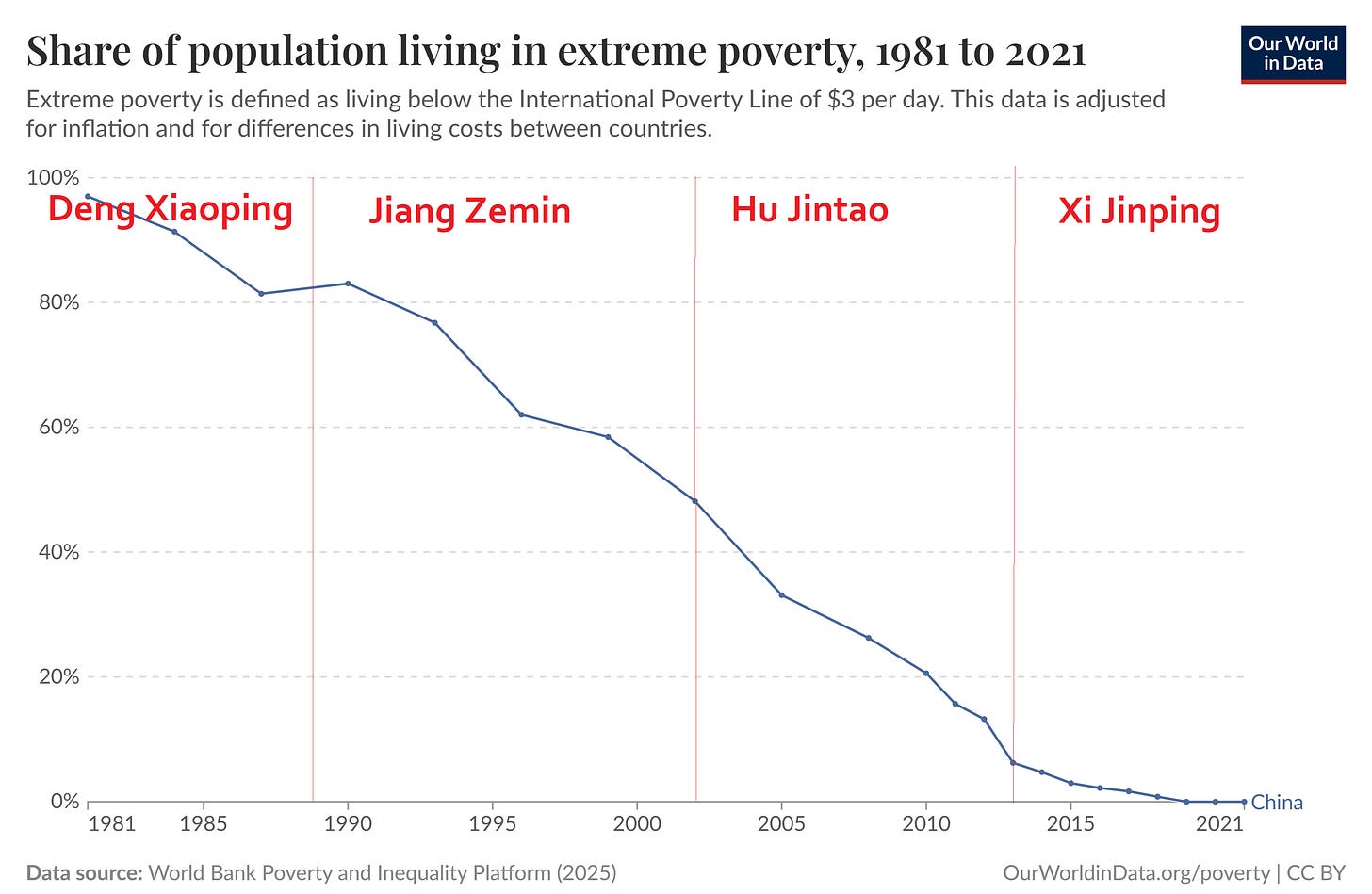

In 2021, when Xi announced “complete victory” in eradicating absolute poverty in China, he took the plaudits. “This is the result of the efforts of two generations of people led by the CPC since the 1980s, especially over the past eight years,” said Global Times in their write up [emphasis mine]. They would do well to check the data.

Almost half of all China’s extreme poverty reduction happened in the decade under Hu Jintao: just 6% was under Xi.

Look closer too, and you will see the rate noticeably slowed under Xi. At the rate of previous administrations, extreme poverty should have been eradicated in Xi’s first two years, but it took eight — almost as if were pre-destined to coincide with the Party’s First Centenary goal of achieving a “modern socialist country” by 2021.

Cult of personality and the “Chinese Dream”

The undoubted theme of Xi’s early years was of the “Chinese dream” — a phrase he repeated nine times in his first speech to the National People’s Congress.

"We must make persistent efforts, press ahead with indomitable will, continue to push forward the great cause of socialism with Chinese characteristics, and strive to achieve the Chinese dream of great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation."

Xi Jinping, 17 March 2013.

It is beyond question that for most Chinese, life has greatly improved since 2012. What is questionable is by how much. And how much Xi’s tenure has actually contributed.

Under ten years of Hu Jintao, China’s GDP quadrupled.

Under 13 years (and counting) of Xi Jinping, it has less than doubled.

Official messaging from the Party, starting from a Xi speech in 2017, is that this slowdown is deliberate, that the Party is targeting “not high growth, but high quality growth”.

Citizen’s wallets say otherwise.

Under the Hu decade, Chinese people’s disposable incomes went up 3.5 times, averaging growth of over 10 percent per year. Under Xi, that’s halved to 5 percent.

To its cost, the CPC has found there are downsides to taking credit for everything: when things go wrong, blame has nowhere else to go.

Rather than front its mistakes, like a slipping economy, or youth unemployment, Xi has put the onus back on citizens. Telling Chinese in his New Year’s Speech to “work hard”, and previously for the youth to “eat bitterness”.

Today, the phrase “Chinese dream” gets less of an airing. Instead, Xi’s current messaging is very different. To celebrate the 100th anniversary of All-China Federation of Trade Unions, Xi called for “Hard work, unity, and relentless struggle”.

“Let us unite even more closely around the CPC Central Committee,” he conveniently added.

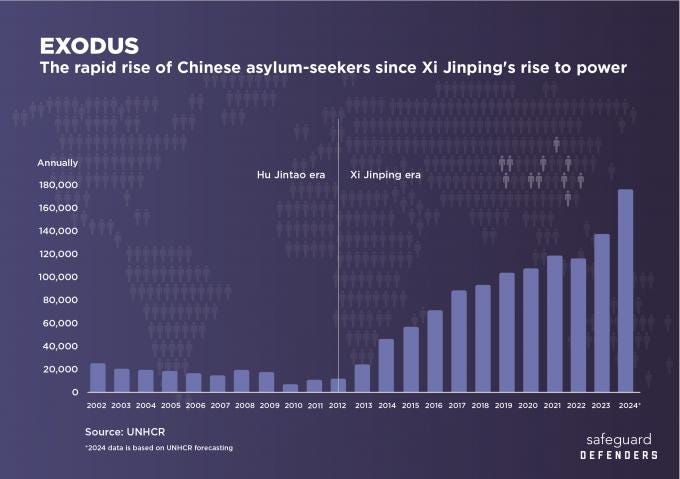

Many citizens disagree. Unable to vote democratically, many are voting with their feet instead.

Record numbers of high-net worth individuals are leaving China. While, according to the UN, over a million Chinese have filed for refugee status internationally since Xi took office — up 1426% since Hu.

A drag on China’s global reputation

Geopolitically, Xi has underdelivered. Arguably, he has taken the country backwards.

Xi inherited a boom period of international relations, that he initially helped improve. The 2015 state visit to the US. A “golden relationship” with the UK. And the historic meeting with Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou in 2015 — the first between leaders of the two Chinese sides since the end of the Civil War in 1949. All spelled good omens.

To cash in, Xi unveiled his grand pet project: the Belt and Road. The launch event in 2017 featured officials from over 130 countries, and 70 international organisations.

However, by the third meet in 2023, so many countries had drifted away, disillusioned with soured investments of the $1 trillion scheme, that leader’s spouses were invited to join the official photo.

Xi’s tenure has been pockmarked with falling outs. India, Japan, and spats with nearly every other geographical neighbour. Some cold wars. Some hot. Covid, Xinjiang, and Hong Kong crackdowns will also surely be filed next to his name: a triumvirate of damaging experiences.

A 2022 Winter Olympics meant to emulate Beijing 2008, ended as a boycotted, political affair, played to empty stadiums amid a pandemic of China’s own making. It was supposed to showcase the “Xi era”. In many ways, it did.

Far from Xi’s halcyon early days, today, China’s closest political allies today read like a coalition of the unloved: Russia, Iran, Hungary, North Korea, Venezuela, Afghanistan…

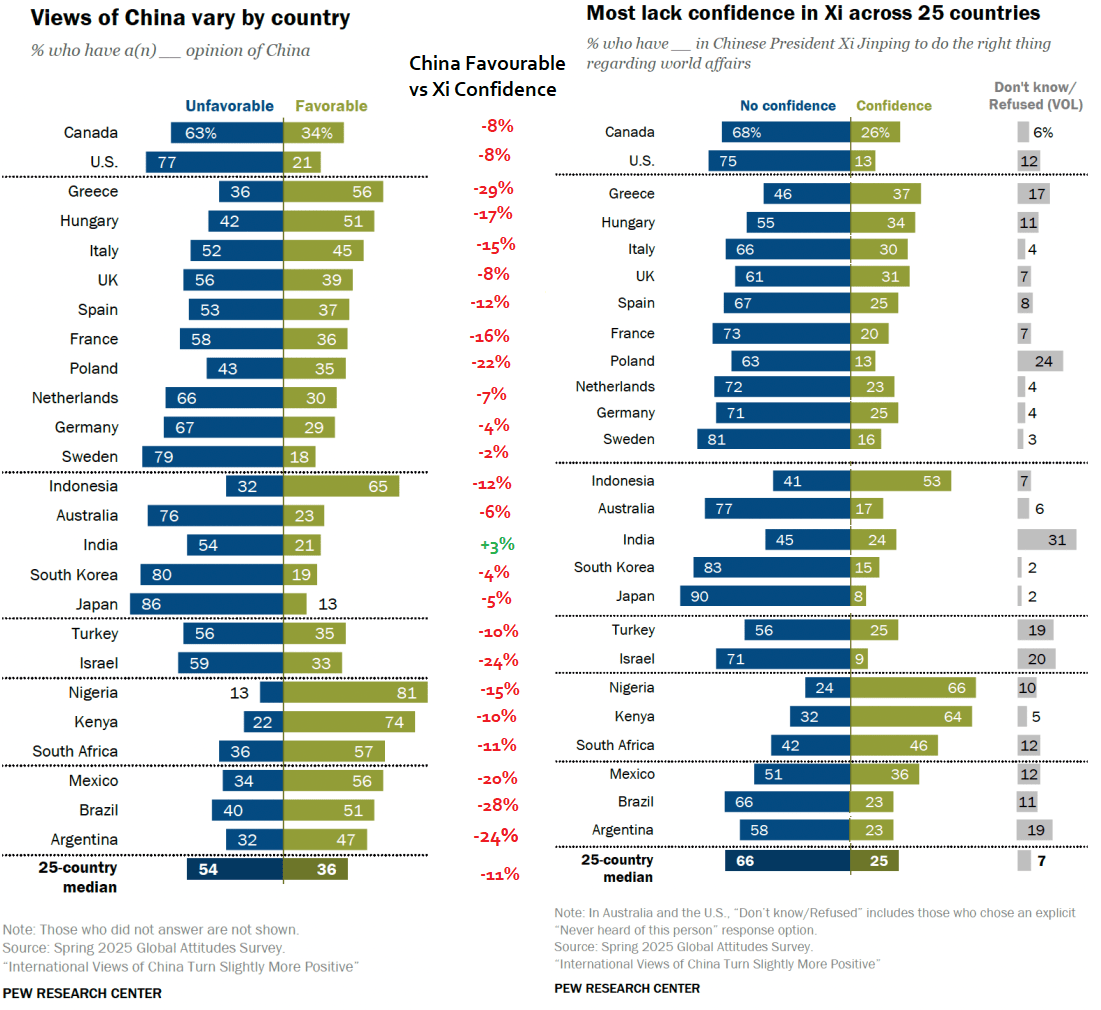

A crude way to analyse Xi’s international effectiveness is to compare global opinion about him, to that of China as a whole.

The bar isn’t high. Under Xi, global public opinion of China dropped to historic lows, which are only just beginning to nudge back up.

By this measure, Xi is a net drag on China’s image, and far from the popular statesman that domestic propaganda regularly portrays. Only India rates Xi more positively.

What’s more damaging, is that some of the biggest differences are to be found among China’s more politically-cultivated partners of recent years, like: Hungary, -17 percent; Brazil, -28 percent; and Greece, -19 percent.

A cynical reading is that these countries are more than happy for China’s attention, flattery, and (crucially) investment — but much less enamored with the government itself.

These days, Xi may lick his wounds over his diminished international status, choosing increasingly to stay at home, than venture abroad to hostile waters that he himself helped foster, preferring to be photographed in Beijing alongside a rump of fellow unelected pariahs and micronations. But as always, outside Zhongnanhai, it’s the people who suffer.

For Chinese citizens, the effects of Xi’s combative, often flawed foreign policy are very real.

While Taiwanese passport holders can visit 138 countries either visa free or on arrival and, Chinese Mainlanders are restricted to just 78.

Overseas, the Chinese are increasingly scrutinised, demonised, and eyed with suspicion. They suffer Asian Hate, which exploded under Covid and in tandem with China’s worsening political reputation. China’s Wolf Warriorism was supposed to inspire pride, help citizens roar — then how come so many Chinese currently feel demure?

But all this is transient, effects that can be overturned via a spate of solid policy, good spin and a dozen Labubus. Effects that are slowly happening. (See before: China is Winning the Media War)

But there is one — wholly unique — aspect to Xi’s tenure. One policy decision that will outlive him, and be remembered by future generations.

Debt.

A ‘bought legacy’

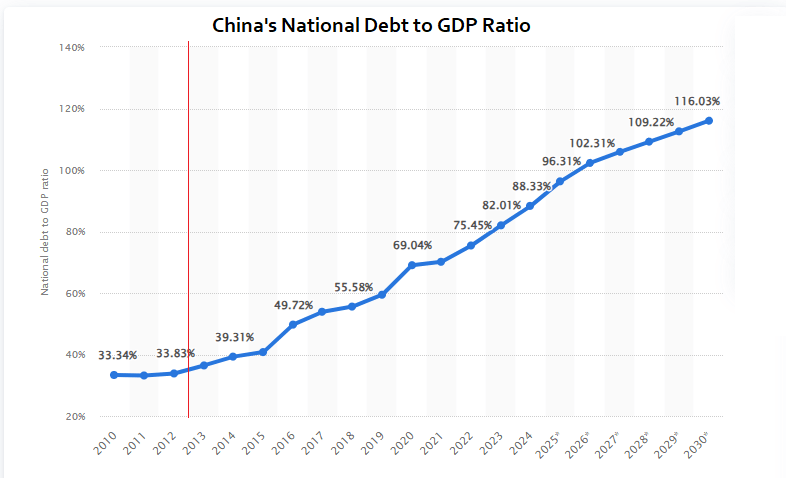

This year, China will borrow $2.50 to create every $1 of growth. This is not normal.

When Xi became President, public borrowing was at around 35% of GDP — a level it had hovered around for decades. Until this point, Beijing’s economic rule was simple: each year, China invested roughly the amount its economy grew by the year before. Growth was organic. Sustainable.

And then Xi took office.

Pick an economic chart, any chart, and it’s easy to spot the year Xi ascended.

Today, official public borrowing is over 90% of GDP, in the Global Top 20, higher than Ukraine, a country which is fighting for its very existence.

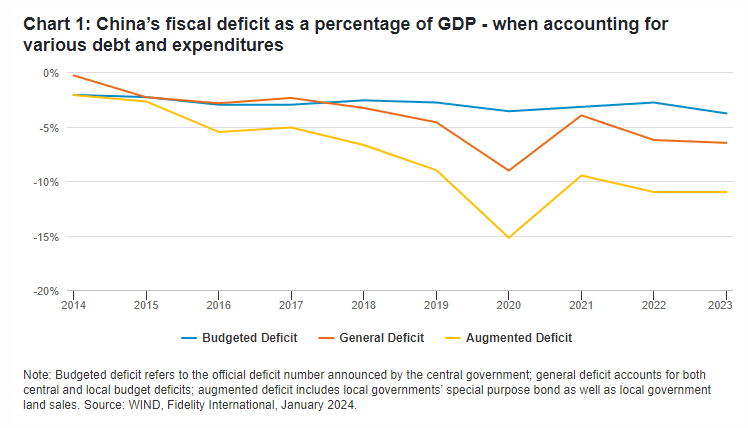

However, this doesn’t include China’s vast Local Government, local government funding vehicles (LGFVs), and bonds — a scheme now increasingly being used to plug holes where land sales used to be. Since 2020, official numbers show local government debt has doubled.

Include all this and China’s total debt burden hit 312 percent of GDP last year, making China one of the most indebted nations on the planet, rivalling the US, Greece and Japan.

Indeed, for a vision of its possible future, China need only look across the waves at its Japanese neighbour: a once technological hotspot, stuck in a deflationary spiral, saddled with zombie debt, and a shrinking, aging and nihilistic population.

More concerning is how this borrowing is quickening — not slowing.

Officially, China’s deficit was 3 percent of GDP last year, and will be 4 percent this year. Again, include local borrowing and the like, and the PRC’s true deficit is actually well over 10 percent.

It’s worth pausing to remind ourselves again: this is a completely new phenomenon in China, and absolutely unique to the Xi era.

A harsh view is that Xi has sought to buy his legacy. In a constant quest for “good news” and to ignite a spluttering economy, the Chairman is burning future funds in order to sustain the illusion of present success.

Ironically, this dash could be the poison pill that ultimately destroys Xi’s name.

There exists a future where the Government can no longer fund endless expansion through credit; where much vaunted Chinese innovation fails to deliver expected new markets; where domestic consumption hits a natural ceiling, as Chinese shoppers tire of their new commercialism, or simply can’t afford it; and the effects of China’s dwindling population and aging society begin to bite economically. A great economic freeze, a cultural plateau.

With the credit card maxed out, and all easy infrastructure wins exhausted, it is not inconceivable there is a future where the Chinese Government is financially hamstrung, needing to implement politically unpopular tax rises, or spending cuts. As they wring and scrimp, perhaps they will rue their previous president’s will to spelunk all of China’s once low debt cushion, across just a decade.

Not publicly — that’s not in the CPC’s nature, admitting missteps — but you can certainly imagine the Beijing choosing collective amnesia over Xi’s profligate years; much as how they today hush Mao’s land reforms, or Deng’s handling of 1989.

Is this to be Xi’s greatest legacy?

It’d be fitting. The son of a Party elder, groomed into power, and who spent other’s money on flashy toys for show, with reckless abandon.

In many ways, Xi Jinping is the ultimate fuerdai.

All the points you raise are completely valid but I don't really see the current sentiment in China coming to the same conclusions (yet). This is all completely anecdotal and limited to my China bubble but I feel like many people in China would have various answers for what Xi's legacy is: anti-corruption, elevating China's image abroad (as you pointed out in your excellent last article re the media wars), acceleration AI innovation (deepseek's "Sputnik moment"), making excellent use of rare earths as leverage in the trade wars, dominating the renewables sector - in short, making China great again. Almost none of my Chinese friends have any desire to emigrate to the US or Europe anymore, and those who study abroad mostly return to China immediately (again, totally anecdotal but that's what I'm observing right now). Incidentally, almost none of my friends have much love for Xi as a leader but they do feel like China is in a better position than it used to be even if they themselves are not (as you pointed out, high youth unemployment, deflationary pressures etc). It really all comes down to whether Xi's debt gamble will come back to haunt him and somehow undo the progress China has made on the world stage - he might either reap all the glory or all the blame.

Interesting article, I was just thinking the other day about how unsuccessful Xi seems to have been in building any sort of a personality cult, very rarely do you hear people singing his praises outside of official (and perhaps corporate) material, he barely ever pops up on my WeChat moments.

Small correction: the China favorable vs Xi confidence gap for Greece is 19, not 29